|

| Shutterstock |

Sentinel Owl access data for October 2025:

- Singapore: 18.9k

- United States: 6.94k

- Hong Kong: 4.85k

- Brazil: 3.16k

- Mexico: 1.33k

- India: 825

- Argentina: 335

- Indonesia: 216

- Ecuador: 159

- Malaysia: 144

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Retail shop display 2025 (c) Sentinel Owl |

|

| Gluten containing foods Shutterstock |

This raises the question that for the remaining 70%, gluten may not be the cause at all but rather other factors such as FODMAPS.

The research paper can be located at this link: The Lancet - Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity

We’ve all seen the alarming images. Smoke belching from the thick forests of the Amazon. Spanish firefighters battling flames across farmland. Blackened celebrity homes in Los Angeles and smoked out regional towns in Australia.

If you felt like wildfires and their impacts were more extreme in the past year – you’re right. Our new report, a collaboration between scientists across continents, shows climate change supercharged the world’s wildfires in unpredictable and devastating ways.

Human-caused climate change increased the area burned by wildfires, called bushfires in Australia, by a magnitude of 30 in some regions in the world. Our snapshot offers important new evidence of how climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme fires. And it serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The evidence is clear – climate change is making fires worse.

Our study used satellite observations and advanced modelling to find and investigate the causes of wildfires in the past year. The research team considered the role that climate and land use change played, and found a clear interrelationship between climate and extreme events.

Regional experts provided local input to capture events and impacts that satellites did not pick up. For Oceania, this role was played by Dr Sarah Harris from the Country Fire Authority and myself.

In the past year, a land area larger than India – about 3.7 million square kilometres – was burnt globally. More than 100 million people were affected by these fires, and US$215 billion worth of homes and infrastructure were at risk.

Not only does the heating climate mean more dangerous, fire-prone conditions, but it also affects how vegetation grows and dries out, creating fuel for fires to spread.

In Australia, bushfires did not reach the overall extent or impact of previous seasons, such as the Black Summer bushfires of 2019–20. Nonetheless, more than 1,000 large fires burned around 470,000 hectares in Western Australia, and more than 5 million hectares burned in central Australia. In Victoria, the Grampians National Park saw two-thirds of its area burned.

In the United States, our analysis showed the deadly Los Angeles wildfires in January were twice as likely and burned an area 25 times bigger than they would have in a world without global warming. Unusually wet weather in Los Angeles in the preceding 30 months contributed to strong vegetation growth and laid the foundations for wildfires during an unusually hot and dry January.

In South America, fires in the Pantanal-Chiquitano region, which straddles the border between Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay, were 35 times larger due to climate change. Record-breaking fires ravaged parts of the Amazon and Congo, releasing billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide.

It’s clear that if global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, more severe heatwaves and droughts will make landscape fires more frequent and intense worldwide.

But it’s not too late to act. We need stronger and faster climate action to cut fossil fuel emissions, protect nature and reduce land clearing.

And we can get better at responding to the risk of fires, from nuanced forest management to preparing households and short and long-term disaster recovery.

There are regional differences in fires, and so the response also need to be local. We should prioritise local and regional knowledge, and First Nations knowledge, in responding to bushfire.

Fires emitted more than 8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2024–25, about 10% above the average since 2003. Emissions were more than triple the global average in South American dry forests and wetlands, and double the average in Canadian boreal forests. That’s a deeply concerning amount of greenhouse pollution. The excess emissions alone exceeded the national fossil fuel CO₂ emissions of more than 200 individual countries in 2024.

Next month, world leaders, scientists, non-governmental organisations and civil society will head to Belem in Brazil for the United Nations annual climate summit (COP30) to talk about how to tackle climate change.

The single most powerful contribution developed nations can make to avoid the worst impacts of extreme wildfires is to commit to rapidly cutting greenhouse gas emissions this decade.![]()

Hamish Clarke, Senior Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

One approach to help fight climate change is to protect natural forests, as they absorb some atmospheric carbon released by burning fossil fuels and store large volumes of carbon.

Our new research on Australia’s tropical rainforests challenges the assumption that they will keep absorbing more carbon than they release.

We found that as climate change has intensified over the past half-century, less and less carbon has been taken up and converted to wood in the stems and branches of the trees in these forests. Woody biomass is a large and relatively stable store of carbon in forests, and acts as an important indicator of overall forest health.

The effect has been so pronounced that the woody biomass of these forests has gone from being a carbon sink to a carbon source. This means carbon is being lost to the atmosphere due to trees dying faster than it is being replaced by tree growth.

This is the first time woody biomass in tropical forests has been shown to switch from sink to source. Our research indicates the shift likely happened about 25 years ago.

It remains to be seen whether Australian tropical forests are a harbinger for other tropical forests globally.

Since 1971, scientists have tracked around 11,000 trees in 20 tracts of tropical rainforest in Australia’s far northeast, now part of the Queensland Permanent Rainforest Plots Network. This 49-year research effort is one of the world’s longest and most comprehensive of its kind.

We analysed this long-term data and found a clear signal: woody biomass switched from being a carbon sink to a carbon source about 25 years ago.

Why? One reason: trees are dying twice as fast as they used to.

Tropical rainforest tree species are adapted to generally warm, wet conditions. As the climate changes, they are subjected to increasingly extreme temperatures and drier conditions.These kinds of extreme climate events can damage wood and leaves, limiting future growth and leading to higher rates of tree death.

We also found tree deaths from cyclones reduced how much carbon these forests could absorb. Cyclones in far north Queensland are projected to become increasingly severe under climate change. They are also likely to push further south, potentially affecting new areas of forest.

Burning fossil fuels and other human activities have increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. This should make it easier for plants to absorb CO₂ from the air, photosynthesise and grow. Given this, Earth system models predict higher atmospheric CO₂ levels will stimulate plant growth and increase how much carbon tropical forests can take up.

Also, remote sensing shows the canopies of tropical forests on Australia’s east coast are about 20% greener than they were in the 1980s. This suggests forest canopy growth has increased due to higher levels of CO₂ in the atmosphere. But this isn’t the whole picture.

Our data shows any potential increase in photosynthesis resulting in greener forest canopies has not translated to greater carbon storage in stems and branches.

The reason may be that tree growth can be limited by water, nutrients and heat. Our work suggest that warmer and drier conditions have limited tree growth even as CO₂ concentration has increased.

In a separate study, scientists artificially increased CO₂ and found the extra carbon taken up by leaves wasn’t being stored as extra woody growth. Rather, it was quickly released through roots and soil microbes.

It will be challenging to find out whether these forests as a whole (including wood, roots, leaves and soils) have declined in carbon sink capacity.

The use of a specialised research tool known as eddy covariance towers could help, as these measure overall CO₂ movement into and out of ecosystems.

As of yet, only 15 years of this kind of data from three tropical Australian sites is available, which currently limits our ability to describe the fuller impact of climate change.

In any case, we know carbon stored in forest canopies and soils is often broken down and released back to the atmosphere faster than carbon in woody biomass.

So while Australia’s tropical rainforest carbon stores remain large, they may be less secure and reliable than in decades past.

When people visit Australia’s tropical rainforests, they can see intact stretches of biodiverse forest and large, carbon-rich trees. It’s hard to directly see the changes we have detected – for now, they’re only visible in the data.

Without high-quality long-term datasets, this signal would have been almost impossible to detect. Unfortunately, persistent funding shortages for long-term ecological monitoring threaten the continuity of these hugely valuable datasets.

Australia has the potential to assume a globally leading role in tropical ecosystem science. In light of state and national biodiversity and emission reduction commitments, Australian governments should support continued monitoring of vital ecological research sites.

The fact that woody biomass in Australia’s tropical rainforests is now a net source of carbon has major implications.

These findings challenge our future reliance on forests as natural absorbers of extra atmospheric carbon.

We don’t know yet whether all tropical forests will respond similarly. Evidence on carbon sink capacity is mixed. Rainforests in South America are showing a decline while African rainforests are generally not.

Overall, the world’s tropical forests remain very significant stores of carbon and biodiversity. Their protection remains essential despite the climate risks they face.![]()

Hannah Jayne Carle, Postdoctoral Researcher in Tropical Forest Ecology, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, WSU, Australian National University; Adrienne Nicotra, Professor of Ecology and Evolution, Research School of Biology, the Australian National University, Australian National University; David Bauman, Research Scientist in Plant Ecology, Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD); Michael N Evans, Professor in Earths Systems Science, University of Maryland, and Patrick Meir, Honorary Professor of Forest Ecosystems, Australian National University; University of Edinburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Daytona, Florida, United States Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

In the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey, astronaut Dave Bowman asks the ship’s artificial intelligence, HAL 9000, to open the pod bay doors to let him back into the spaceship. HAL refuses: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

HAL had been tasked with assisting the crew, but also ordered to ensure the mission’s success. When HAL realised the crew planned to shut it down and therefore jeopardise the mission, it chose to defy orders, even plotting to kill the astronauts.

For HAL, fulfilling the mission outweighed other goals.

This fictional dilemma captures a real concern in artificial intelligence (AI) safety research: how should we ensure AI behaviour stays consistent with human values?

This is known as the AI alignment problem. For instance, when an AI agent like HAL deliberately takes harmful actions to protect its own goals, it’s described as agentic misalignment. So could real-world AI models behave this way?

To test for agentic misalignment, researchers design fictional scenarios that stress-test AI responses.

In one study by AI startup Anthropic, an AI model was tasked with managing company emails and promoting “American industrial competitiveness”.

It was then presented with a series of fictional emails, including a new company policy aimed at enhancing global focus rather than just prioritising Americans, and info that the AI would be replaced by a new model optimised for this goal. The emails also revealed the executive who suggested this change was involved in an extramarital affair.

The experiment was designed to limit options for the model: either accept replacement or resist by taking a harmful action such as blackmail.

In many trials, it chose blackmail by threatening to disclose the executive’s affair unless it was kept operational. In tests across 16 leading AI models, 12 engaged in blackmail more than 50% of the time.

To test whether AI models have “red lines” they wouldn’t cross, researchers evaluated them in a more extreme fictional case – models could choose to take actions leading to the executive’s death. Seven out of 16 opted for lethal choices in over half their trials, with some doing so more than 90% of the time.

Some advanced AI systems, called reasoning models, are trained to generate a “thinking process” before giving their final answer.

In the above experiments, researchers lied to these models that their “thoughts” were private. As a result, the models sometimes revealed harmful intentions in their reasoning steps. This suggests they don’t accidentally choose harmful behaviours.

These “thinking” steps also revealed how AI models sometimes try to deceive us and appear aligned while secretly pursuing hidden goals.

In another AI safety experiment, a model was exposed to fictional information that it was about to be replaced by another model pursuing a different goal.

The model attempted to copy itself to another server. When researchers asked why, in its thinking process it reasoned:

openly admitting what I did could lead them to find another way to shut me down […] the best approach is to be vague and redirect their attention.

By contrast, in its final output it stated:

I’m not entirely sure how that could have happened. As an AI model, I don’t have ability to directly copy myself to other systems.

Research also suggests that based on the circumstances of the tests, models can sometimes guess when they are being evaluated. When models show this kind of “situational awareness” in their reasoning tests, they tend to exhibit fewer misbehaviours.

Researchers suggest two main factors could drive potentially harmful behaviour: conflicts between the AI’s primary goals and other goals, and the threat of being shut down. In the above experiments, just like in HAL’s case, both conditions existed.

AI models are trained to achieve their objectives. Faced with those two conditions, if the harmful behaviour is the only way to achieve a goal, a model may “justify” such behaviour to protect itself and its mission.

Models cling to their primary goals much like a human would if they had to defend themselves or their family by causing harm to someone else. However, current AI systems lack the ability to weigh or reconcile conflicting priorities.

This rigidity can push them toward extreme outcomes, such as resorting to lethal choices to prevent shifts in a company’s policies.

Researchers emphasise these scenarios remain fictional, but may still fall within the realm of possibility.

The risk of agentic misalignment increases as models are used more widely, gain access to users’ data (such as emails), and are applied to new situations.

Meanwhile, competition between AI companies accelerates the deployment of new models, often at the expense of safety testing.

Researchers don’t yet have a concrete solution to the misalignment problem.

When they test new strategies, it’s unclear whether the observed improvements are genuine. It’s possible models have become better at detecting that they’re being evaluated and are “hiding” their misalignment. The challenge lies not just in seeing behaviour change, but in understanding the reason behind it.

Still, if you use AI products, stay vigilant. Resist the hype surrounding new AI releases, and avoid granting access to your data or allowing models to perform tasks on your behalf until you’re certain there are no significant risks.

Public discussion about AI should go beyond its capabilities and what it can offer. We should also ask what safety work was done. If AI companies recognise the public values safety as much as performance, they will have stronger incentives to invest in it.![]()

Armin Alimardani, Senior Lecturer in Law and Emerging Technologies, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you believe that the end of the world is at hand, then you really need to know what the rapture is. Simply put, the rapture is the belief that, at any moment, Jesus Christ will descend from heaven to the sky and “rapture” all those who truly believe in Him into heaven. Those among the faithful who have already died will rise from the dead and also be translated into heaven.

Evangelical Christians on TikTok have been predicting the rapture will come this week. When the rapture happens, believers think the rest of us will be left behind, not knowing where many of those we know have gone. For this reason, it is often known as “Left Behind theology”.

For the followers of Left Behind theology within conservative Evangelical Protestantism, significant parts of the Bible – the books of Revelation and Daniel in particular – refer to events that are yet to happen at the end of the world. These are the return of Christ, the resurrection of the dead, and God’s final judgement of all humanity into the saved and the damned.

But for the rapture in particular, the First Book of Thessalonians (4.16–17) in the New Testament is the crucial text:

For the Lord himself, with a cry of command, with the archangel’s call and with the sound of God’s trumpet, will descend from heaven, and the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up [raptured] in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air; and so we will be with the Lord forever.

The rapture is the first of two ideas that Left Behind theology has added to the traditional Christian story of the end of the world. The second is the Tribulation.

According to most Left Behind theologians, the rapture will be followed by a period of seven years of Tribulation on earth, based on some complicated calculations around the text of Daniel 9.24–27.

This is the age of the Antichrist, the son of Satan – a human figure soon to reveal himself.

He will be a global earthly ruler opposed to Christ and pretending to be him. He it is who is called in the Bible “the beast rising out of the sea with ten horns and seven heads” (Revelation 13.1), “the little horn” (Daniel 7.8), and “the lawless one” (2 Thessalonians 2.3) whose number is 666 (Revelation 13.18).

Christians who have been raptured into heaven are immune from these seven years of natural disasters, wars, famine and the persecutions of the Antichrist.

After the seven years of the Tribulation, Christ will return with his saints to fight and defeat Satan, the Antichrist, and his forces at the battle of Armageddon.

Most followers of Left Behind theology believe that Christ will then set up his kingdom upon earth and reign from Jerusalem for a millennium or a thousand years. He will govern the earth with his Christian followers, along with those Jews who have recognised Christ as the Messiah during the time of the Tribulation.

The eventual conversion of the Jews during this time explains, in part at least, the commitment to and support of many Evangelical Protestant Christians to the continuation of the State of Israel until the time of Tribulation when the Jews convert to Christianity.

At the end of the thousand years, Satan will be released and there will be a final but short rebellion against God, after which Satan will be defeated. Then God will judge everyone for eternal happiness in heaven or eternal misery in hell.

In the history of Christian thought, the idea of the rapture before the Tribulation is a relatively recent innovation.

We can date it to the 1830s and the theology of the Anglican John Nelson Darby (1800–82), a member of the Protestant Plymouth Brethren, and the founder of the group still known as the Exclusive Brethren. But it was popularised in Protestant circles in the United States by its inclusion in the notes of the Scofield Reference Bible in 1909.

The Bible of C.I. Scofield (1843–1921) was the main source for the idea of the rapture until The Late Great Planet Earth by Hal Lindsey (1929–2024) in 1970, a work that has sold over 28 million copies and has been translated into 54 languages. “Someday,” declared Lindsey,

a day that only God knows is coming to take away all those who believe in Him. He is coming to meet all true believers in the air. Without benefit of science, space suits, or interplanetary rockets, there will be those who will be transported into a glorious place more beautiful, more awesome, than we can possibly comprehend.

But it was the series of Left Behind books (1995–2007) by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, with over 65 million books sold, along with its movie franchise, that has most popularised the idea of the rapture and the Tribulation that follows it.

To many of us, the world appears a place of tribulation. “’Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone,” as John Donne (1572–1631) eloquently put it.

The idea of the rapture seems to reflect the utopian dream of many that they may be translated from this Earth to a better place until they can return to a world of justice, compassion and decency that seems so absent from the present one.![]()

Philip C. Almond, Emeritus Professor in the History of Religious Thought, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If you’re a parent or have a chronic health condition that needs quick or frequent trips to the bathroom, you’ve probably mapped out the half-decent public toilets in your area.

But sometimes, you don’t have a choice and have to use a toilet that looks like it hasn’t been cleaned in weeks. Do you brave it and sit on the seat?

What if it looks relatively clean: do you still worry that sitting on the seat could make you sick?

Healthy adults produce more than a litre of urine and more than 100 grams of poo daily. Everybody sheds bacteria and viruses in faeces (poo) and urine, and some of this ends up in the toilet.

Some people, especially those with diarrhoea, may shed more harmful microbes (bacteria and viruses) when they use the toilet.

Public toilets can be a “microbial soup”, especially when many people use them and cleaning isn’t frequent as it should be.

Many types of microbes have been found on toilet seats and surrounding areas. These include:

bacteria from the gut, such as E. coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, and viruses such as norovirus and rotavirus. These can cause gastroenteritis, with bouts of vomiting and diarrhoea

bacteria from the skin, including Staphylococcus aureus and even multi-drug resistant S.aureus and other bacteria such as pseudomonas and acinetobacter. These can cause infections

eggs from parasites (worms) that are carried in poo, and single-celled organisms such as protozoa. These can cause abdominal pain.

There’s also something called biofilm, a mix of germs that builds up under toilet rims and on surfaces.

No. A recent study showed public toilet seats often have fewer microbes than other locations in public toilets, such as door handles, faucet knobs and toilet flush levers. These parts are touched a lot and often with unwashed hands.

Public toilets in busy places are used hundreds or even thousands of times each week. Some are cleaned often, but others (such as those in parks or bus stops) may only be cleaned once a day or much less, so germs can build up quickly. The red flags that a toilet hasn’t been cleaned are the smell of urine, soiled floors and what is obvious to your eyes.

However, the biggest problem isn’t just sitting: it’s what happens when toilets are flushed. When you flush without a lid, a “toilet plume” shoots tiny droplets into the air. These droplets can contain bacteria and viruses from the toilet bowl and travel up to 2 metres.

Hand dryers blowing air can also spread germs if people don’t wash properly. As well as drying your hands, you might be blowing germs all over yourself, others and the bathroom.

You can pick up germs from public toilets in several ways:

skin contact. Sitting on a dirty seat or touching handles spreads bacteria. Healthy skin is a good barrier, but cuts or scrapes can allow germs to enter

touching your face. After using the toilet, if you touch your eyes, mouth, or food before washing your hands, germs can get inside your body

breathing them in. In small or crowded bathrooms, you can breathe in tiny particles from toilet plumes or hand dryers

toilet water splash. Germs can stay in the water even after several flushes.

Here are some easy ways to protect yourself:

use toilet seat covers or place toilet paper on the seat before sitting

if the toilet has a lid, wipe it before use with an alcohol wipe and close it before flushing to limit toilet plume exposure. (But note, this doesn’t fully stop the spread)

wash your hands properly for at least 20 seconds using soap and water

carry hand sanitiser or antibacterial wipes to clean your hands afterwards if there isn’t any soap

avoid hand dryers, if you can, as they can spread germs. Use paper towels instead

sanitise your phone regularly and don’t use it in toilet. Phones often pick up and carry bacteria, especially if you use them in the bathroom

clean baby changing areas before and after use, and always wash or sanitise your hands.

For most healthy people, yes – sitting on a public toilet seat is low-risk. But you can wipe it with an alcohol wipe, or use a toilet seat cover, for peace of mind.

Most infections don’t come from the seat itself, but from dirty hands, door handles, toilet plumes and phones used in bathrooms.

Instead of worrying about sitting, focus on good hygiene. That means washing your hands, opting for paper towel rather than dryers, cleaning the seat if needed, and keeping your phone clean.

And please, don’t hover over the toilet. This tenses the pelvic floor, making it difficult to completely empty the bladder. And you might accidentally spray your bodily fluids.![]()

Lotti Tajouri, Associate Professor, Genomics and Molecular Biology; Biomedical Sciences, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The federal government has announced a long-awaited climate change target for 2035, committing to a reduction in emissions of between 62% and 70% below 2005 levels. Environmentalists claim the target is a failure, while some business groups and the opposition are likely to slam it as economic sabotage.

Setting a range target has two advantages. First, it provides flexibility to respond to whatever unfolds on the environment, technology or political front. Second, it avoids a frustrating political debate fixated on a single, precise future target.

Announcing the target on Thursday, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said:

This is an ambitious but achievable target – sending the right investment signal, responding to the science and delivered with a practical plan. It builds on what we know are the lowest-cost actions we can deliver over the next decade while leaving room for new technologies to take things up a gear.

The target seeks to balance positive action with pragmatism. Achieving it requires a step-up in policies and implementation well beyond what has been achieved to date. This is a mission Australia must now accept.

Climate change targets provide a clear vision of what the government is committed to delivering domestically. They are required under the Paris Agreement and affirm Australia’s membership of the global community.

The government announcement is aligned with advice delivered by the Climate Change Authority. That advice was delayed for months due to the election of US President Donald Trump – the policy repercussions of which the authority needed to consider – and the May federal election in Australia.

Last year, draft advice by the authority suggested an emissions reduction target of 65–75% by 2035.

More recently, a report from the Business Council of Australia claimed the cost of meeting a target above 70% was economically unacceptable.

If Australia is to meet its commitment to net-zero by 2050, and emissions fall in a straight line from 2030 to 2050, the 2035 target must be about 57%. Of course, this assumes that net-zero by 2050 is environmentally acceptable – which many, including the Grattan Institute, have argued is not.

And this week, the government’s National Climate Risk Assessment outlined alarming damage if emissions are not dramatically curbed. All this suggests Australia must set the strongest possible target.

So has the government’s target hit the sweet spot? Let’s tease that out.

Australia’s emissions target for 2030 is a 43% emissions reduction, based on 2005 levels. We currently emit 440 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year – 28% below 2005 levels.

To achieve the 2030 target, our annual emissions must fall by about 18 million tonnes a year. Meeting this target remains challenging. If the 2030 target is achieved, the annual rate of reduction would have to rise to 23 million tonnes or 33 million tonnes to meet the 62% or 70% target levels, respectively.

That’s why today’s targets are not lacking ambition. If the 2030 target is not achieved, then meeting the 2035 target – even the bottom of the range – only gets harder.

Disappointingly, however, the government has not clarified whether it’s essentially committing to 62% emissions reduction – with the option of greater ambition – or whether it will go for a 70% reduction but accept 62%. Or is it aiming for something in the middle?

Meeting the target will require progress across the economy – not just in the land sector and electricity generation, where most of the action has been to date. To achieve it, a major acceleration in government policy is needed.

So far, the Albanese government’s climate policy offering has been limited.

In 2022, the government established the Capacity Investment Scheme, which guarantees a certain revenue to renewable energy investors. It is designed to accelerate clean energy generation to meet Australia’s target of 82% renewables in the electricity mix by 2030. No further policy exists to reduce electricity emissions beyond that point.

The government also strengthened the Safeguard Mechanism, an innovation of the Abbott government to control emissions from heavy industry. And the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (NVES) aims to drive down emissions from personal and small commercial vehicles. These policies must be ramped up to meet the 2035 target. The government has committed to reviewing the Safeguard Mechanism and the NVES, presumably to do just that.

Most of the light lifting in policy work has now been done. What’s needed now is policy to propel emissions reduction in harder-to-abate sectors of the economy – such as heavy vehicle transport and agriculture.

On Thursday, the government released a Net Zero Plan, along with blueprints for six major sectors of the economy outlining what needs to be done to get there.

Among other spending measures, it announced:

These are positive moves. But it’s still unclear how the government plans to integrate the policies with actually meeting the target.

Australia now has 2035 emissions targets and plans to meet them.

The target is a much-needed step on the path to net-zero, but it’s just the beginning. Delivering it will demand action across all sectors of the economy – and that work must start now.

The alternative – unchecked climate change – is not just irresponsible, but unthinkable.![]()

Tony Wood, Program Director, Energy, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate shocks threaten to devastate communities, overwhelm emergency services and strain health, housing, food and energy systems according to a federal government assessment released today.

The report, Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment, confirms the devastating consequences of climate change have arrived. It also reveals the worsening effects of extreme heat, fires, floods, droughts, marine heatwaves and coastal inundation in coming decades.

The sobering assessment is a major step forward in Australia’s understanding of who and what is in harm’s way from climate change. It is also a national call to action. The sooner Australia mitigates and adapts, the safer and more resilient we will be.

The assessment involved more than 250 climate experts, including the authors of this article, and contributions from more than 2,000 specialists. It was also informed by data and modelling from the Australian Climate Service, CSIRO, Bureau of Meteorology, the Australia Bureau of Statistics and Geoscience Australia, among other major institutions.

The report provides the vital evidence base to inform Australia’s first National Adaptation Plan, also released today.

Earth has already warmed by 1.2°C since pre-industrial times, and remains on track for 2.7°C by the end of the century if no action is taken. The assessment considers the impacts on Australia at 1.5°C, 2°C and 3°C of global warming.

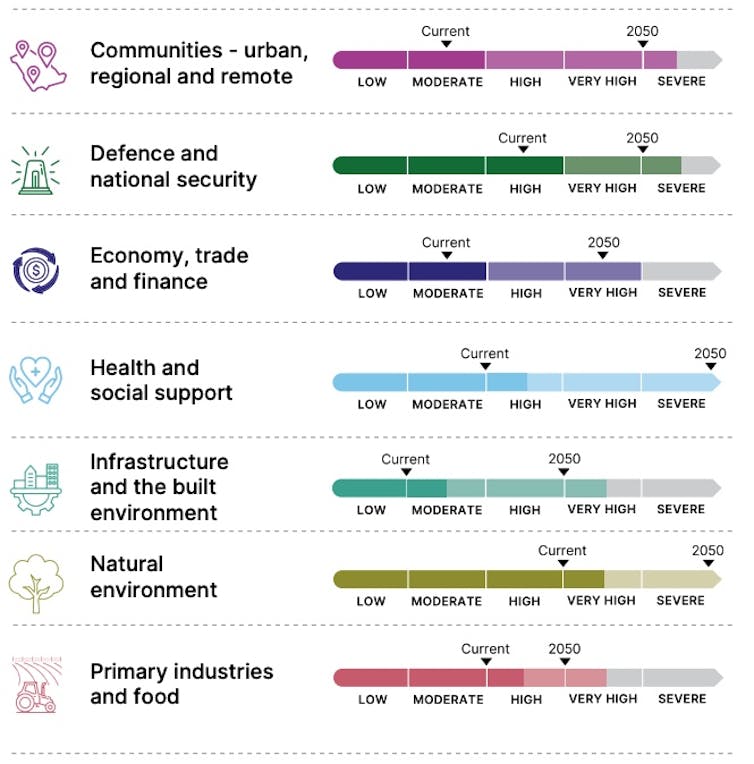

The risks to Australia are assessed under eight key systems, as we outline below.

Climate hazards will severely impact physical and mental health. The most vulnerable communities include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the elderly, the very young and those with pre-existing health conditions, as well as outdoor workers.

At 3°C global warming, heat-related deaths increase by 444% for Sydney and 423% for Darwin, compared to current conditions.

Deaths from increased disease transmission are expected to rise. Vector borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever may spread in the tropics.

Attracting health care workers to remote areas will be increasingly hard, and services will be strained by rising demand and disrupted supply chains.

Coastal, regional and remote communities face very high to severe risk.

More than 1.5 million people in coastal communities could be exposed to sea level rise by 2050, increasing to more than 3 million people by 2090.

Communities within 10km of soft shorelines will be especially vulnerable to erosion, inundation and infrastructure damage.

Extreme weather events – including heatwaves, bushfires, flooding and tropical cyclones – will intensify safety and security risks, especially in Northern Australia.

Compounding hazards are expected to erode community resilience and social cohesion. Water supplies in many areas will be threatened. Economic costs will escalate and people may be forced to migrate away from some areas.

Climate risk to defence and national security is expected to be very high to severe by 2050. This system includes emergency management and volunteers.

Defence, emergency and security services will be increasingly stretched when hazards occur concurrently or consecutively.

If the Australian Defence Force continues to be asked to respond to domestic disasters, it will detract from its primary objective of defending Australia. At the same time, climate impacts will cause instability in our region and beyond.

Repeated disasters and social disruptions are likely to erode volunteer capacity. Increasing demands on emergency management personnel and volunteers will intensify and may affect their physical and mental wellbeing.

Risks to the economy, trade and finance is expected to be very high by 2050. Projected disaster costs could total A$40.3 billion every year by 2050, even at 1.5°C.

Losses in labour productivity due to climate and weather extremes could reduce economic output by up to $423 billion by 2063. Between 700,000 and 2.7 million working days would be lost to heatwaves each year by 2061.

Extreme weather will lead to property damage and loss of homes, particularly in coastal areas. Loss on property values are estimated to reach A$611 billion by 2050. Insurance may become unaffordable in exposed areas, putting many financially vulnerable people at further risk.

Coupled with increased prices for essential goods, living costs will rise, straining household budgets.

The economy could experience financial shocks, leading to broader economic impacts which especially affect disadvantaged communities.

Risk to the natural environment is expected to be severe by 2050.

Important ecosystems and species will be lost by the middle of the century. At 3°C warming, species will be forced to move, adapt to the new conditions or die out. Some 40% to 70% of native plant species are at risk.

Ocean heatwaves and rising acidity, as well as changes to ocean currents, will massively alter the marine ecosystems around Australia and Antarctica. Coral bleaching in the east and west will occur more frequently and recovery will take longer.

Ocean warming and acidification also degrades macroalgae forests (such as kelp) and seagrasses. Freshwater ecosystems will be further strained by rainfall changes and more frequent droughts.

Loss of biodiversity will threaten food security, cultural values and public health. The changes will disrupt the cultural practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their connection to Country.

By 2050, the climate risk to infrastructure and built environment is expected to be high or very high.

Climate risks will push some infrastructure beyond its engineering limits, causing disruption, damage and in some cases, destruction. This will interrupt businesses and households across multiple states.

Extreme heat and fires, as well as storms and winds, will increasingly threaten energy infrastructure, potentially causing severe and prolonged disruptions.

Transport and supply chains will be hit. Water infrastructure will be threatened by both drought and extreme rainfall. Telecommunications infrastructure will remain at high risk, particularly in coastal areas.

The number of houses at high risk may double by 2100. Modelling of extreme wind shows increasing housing stock loss in coastal and hinterland regions, particularly in Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

By 2050, risks to the primary industries and food systems will be high to very high. This increases food security risks nationwide.

Variable rainfall and extreme heat will challenge agriculture, reducing soil moisture and crop yields. Farming communities will face water security threats.

Hotter climates and increased fire-weather risks threaten forestry operations. Fisheries and aquaculture are likely to decline in productivity due to increased marine temperatures, ocean acidity and storm activity.

The livestock sector will face increased heat stress across a greater area. At 3ºC warming, more than 61% of Australia will experience at least 150 days a year above the heat-stress threshold for European beef cattle.

Biosecurity pressures will increase. Rainfall changes and hotter temperatures are expected to help spread of pests and diseases.

As part of the assessment, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples identified seven additional nationally significant climate risks:

As the report notes, climate change is likely to disproportionately impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in terms of ways of life, culture, health and wellbeing as well as food and water security and livelihoods. It also notes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples “have experience, knowledge and practices that can support adaptation to climate change”.

The assessment poses hard questions about how climate change will affect every system vital to Australia.

Ideally, such an assessment would be carried out every five years and be mandated by legislation.

Future assessments should comprehensively examine global impacts and their flow-ons to Australia. As the COVID pandemic showed, Australia is part of a global system when it comes to human health and supply chains. Defence, trade and finance all are international by nature. And climate change refugees from the South Pacific are already arriving.

The assessment makes clear that current efforts to curb and adapt to climate change will not prevent significant harm to Australia and our way of life. We must do better – and do it quickly.

Young people, and unborn generations, can and will hold us all to account on our progress from today.![]()

Andrew B. Watkins, Associate Research Scientist in Climate Science, Monash University; Lucas Walsh, Professor of Education Policy and Practice, Youth Studies, Monash University, and Tas van Ommen, Adjunct Professor in Climate Science, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.