|

| Shutterstock |

Sentinel Owl access data for October 2025:

- Singapore: 18.9k

- United States: 6.94k

- Hong Kong: 4.85k

- Brazil: 3.16k

- Mexico: 1.33k

- India: 825

- Argentina: 335

- Indonesia: 216

- Ecuador: 159

- Malaysia: 144

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

German anaesthesiologist Joachim Boldt has an unfortunate claim to fame. According to Retraction Watch, a public database of research retractions, he is the most retracted scientist of all time. To date, 220 of his roughly 400 published research papers have been retracted by academic journals.

Boldt may be a world leader, but he has plenty of competition. In 2023, more than 10,000 research papers were retracted globally – more than any previous year on record. According to a recent investigation by Nature, a disproportionate number of retracted papers over the past ten years have been written by authors affiliated with several hospitals, universities and research institutes in Asia.

Academic journals retract papers when they are concerned that the published data is faked, altered, or not “reproducible” (meaning it would yield the same results if analysed again).

Some errors are honest mistakes. However, the majority of retractions are associated with scientific misconduct.

But what exactly is scientific misconduct? And what can be done about it?

The National Health and Medical Research Council is Australia’s primary government agency for medical funding. It defines misconduct as breaches of the Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research.

In Australia, there are broadly eight recognised types of breaches. Research misconduct is the most severe.

These breaches may include failure to obtain ethics approval, plagiarism, data fabrication, falsification and misrepresentation.

This is what was behind many of Boldt’s retractions. He made up data for a large number of studies, which ultimately led to his dismissal from the Klinikum Ludwigshafen, a teaching hospital in Germany, in 2010.

In another case, China’s He Jiankui was sentenced to three years in prison in 2019 for creating the world’s first genetically edited babies using the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR. His crime was that he falsified documents to recruit couples for his research.

The “publish or perish” culture within academia fuels scientific misconduct. It puts pressure on academics to meet publication quotas. It also rewards them for greater research output, in the form of promotions, funding and recognition. And this can mean research quality is sacrificed for quantity.

But not all research misconduct is premeditated. Some is the result of honest mistakes made by scientists.

For example, Sergio Gonzalez, a young scientist at the Institute for Neurosciences of Montpellier in France, mistakenly uploaded several wrong images to an academic paper and its supplementary material. This didn’t have any effect on the findings of the paper, which were based on the correct images.

But it still represented a case of image duplication and misrepresentation of data. This lead to the journal retracting the paper and launching an investigation. The investigation concluded the breach was unintentional and resulted from the pressures of academic research.

Fewer than 20% of all retractions are due to honest mistakes. Researchers usually contact the publisher to correct errors when they are detected, with no major consequences.

In many countries, an independent national body oversees research integrity.

In the United Kingdom, this body is known as the Committee on Research Integrity. It is responsible for improving research integrity and addressing misconduct cases. Similarly, in the United States, the Office of Research Integrity handles allegations of research misconduct.

In contrast, Australia lacks an independent body directly tasked with investigating research misconduct. There is a body known as the Australian Research Integrity Committee. But it only reviews the institutional procedures and governance of investigations to ensure they are conducted fairly and transparently – and with limited effectiveness. For example, last year it received 13 complaints, only five of which were investigated.

Instead Australia relies on a self-regulation model. This means each university and research institute aligns its own policy with the Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. Although this code originated in medical research, its principles apply across all disciplines.

For example, in archaeology, falsifying an image or deliberately reporting inaccurate carbon dating results constitutes data fabrication. Another common breach is plagiarism, which can also be applied to all fields.

But self-governance on integrity matters is fraught with problems.

Investigations often lack transparency and are carried out internally, creating a conflict of interest. Often the investigative teams are under immense pressure to safeguard their institution’s reputation rather than uphold accountability.

A 2023 report by the Australia Institute called for the urgent establishment of an independent, government-funded research integrity watchdog.

The report recommended the watchdog have direct investigatory powers and that academic institutions be bound by its findings.

The report also recommended the watchdog should release its findings publicly, create whistleblower protections, establish a proper appeals process and allow people to directly raise complaints with it.

The consequences of inadequate oversight are already evident.

One of the biggest research integrity scandals in Australian history involved Ali Nazari, an engineer from Swinburne University. In 2022 an anonymous whistleblower alleged Nazari was part of an international research fraud cartel involving multiple teams.

Investigations cast doubt on the validity of the 287 papers Nazari and the other researchers had collectively published. The investigations uncovered numerous violations, including 71 instances of falsified results, plagiarism and duplication, and 208 instances of self-plagiarism.

Similarly, Mark Smyth, formerly of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research, fabricated research data to support grant applications and clinical trials. An independent inquiry concluded he used his reputation, status and authority to bully and intimidate junior colleagues.

If Australia had a independent research integrity body, there would be a clear governance structure and an established and transparent pathway for reporting breaches at a much earlier stage.

Timely intervention would help reduce further breaches through swift investigation and corrective action. Importantly, consistent governance across Australian institutions would help ensure fairness. It would also reduce bias and uphold the same standards across all misconduct cases.

The call for an independent research integrity watchdog is long overdue.

Only through impartial oversight can we uphold the values of scientific excellence, protect public trust, and foster a culture of accountability that strengthens the integrity of research for all Australians.![]()

Nham Tran, Associate Professor, School of Biomedical Engineering, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

If you’ve ever gone to look up a quick fact and just kept browsing from one article (or page, or video), to another, to another – then you know the feeling of “going down a rabbit hole”. This experience of curiosity-led online wandering has become synonymous with the free, user-created encyclopedia Wikipedia.

Founded in 2001, Wikipedia is today one of the world’s most popular websites. With more users than Amazon, Netflix, TikTok or ChatGPT, the site is a go-to source for people to learn about and discover new interests.

In new research involving more than 480,000 Wikipedia users in 14 languages across 50 countries, US researchers led by Dale Zhou at the University of Pennsylvania studied three distinctly different ways of going down the Wikipedia rabbit hole. These “curiosity styles” have been studied before, but not in such a large, diverse group of people using Wikipedia “naturalistically”, in daily life.

The research may help us better understand the nature and importance of curiosity, its connections to wellbeing, and strategies for preventing the spread of false information.

When Wikipedia was new in the early 2000s, it sparked controversies. People such as librarians and lecturers voiced concerns about Wikipedia’s potential for platforming untrue or incomplete information.

Today, the factuality of Wikipedia’s existing contents is less concerning than questions of bias, such as which topics the site’s volunteer editors deem noteworthy enough to include. There are global efforts to fill gaps in Wikipedia’s coverage, such as “edit-a-thons” to add entries on historically overlooked scientists and artists.

Part of what made Wikipedia groundbreaking was how it satisfies people’s intrinsic learning needs by inviting navigation from page to page, luring readers into rabbit holes. This, combined with the site’s participatory approach to creating and verifying pages, sparked its rapid growth. These qualities have also sustained Wikipedia as a predominant everyday information source, globally.

Research about Wikipedia has also evolved from early studies comparing it to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

This new study examines data about Wikipedia readers’ activities. It looks at the different “architectural styles of curiosity” people embody when they navigate.

The new study explores the “knowledge networks” associated with the three main styles of curiosity: busybody, hunter and dancer. A knowledge network is a visual representation of how readers “weave a thread” across Wikipedia articles.

As the researchers explain:

The busybody scouts for loose threads of novelty, the hunter pursues specific answers in a projectile path, and the dancer leaps in creative breaks with tradition across typically siloed areas of knowledge.

Earlier research had shown evidence of busybodies and hunters, and speculated about the existence of dancers. The new study confirms that busybodies and hunters exist in multiple countries and languages. It also details the dancer style, which has been more elusive to document.

The researchers also identified geographical differences between curiosity styles.

In all 14 languages studied, busybodies tend to read more about culture, media, food, art, philosophy and religion. Hunters in 12 out of 14 languages tend to read more about science, technology, engineering and maths.

In German and English, hunters were more drawn to pages about history and society than busybodies. The opposite was true in Arabic, Bengali, Hindi, Dutch and Chinese.

Dancers were identified by their forward leaps between disparate topics, as well as the diversity of their interests.

The research team points out we still have much to learn about how curiosity is shaped by local norms. Relating these results to gender, ethnicity, access to education, and other elements will paint a fuller picture.

Overall, this study supports the benefits of freer, broader browsing and reading. Following our curiosity can help us become better informed and expand our worldviews, creativity and relationships.

At the same time, people sometimes need closure more than they need exploration. This is not a bad thing or a sign of narrow-mindedness. In many situations there are benefits to moving on from information-seeking, and deciding we’ve learned enough for now.

Endless curiosity can have downsides. This is especially true when it’s motivated not by the joy of learning, but by the discomfort of uncertainty and exclusion. As other research has found, for some people, curiosity can lead toward false information and conspiracy theories. When information has a sense of novelty, or a hint of being hidden by powerful elites, this can make it more appealing, even when it’s not true.

The new study emphasises that different curiosity styles do not lead simply or universally to creativity or wellbeing. People’s contexts and circumstances vary.

Each of us, like Goldilocks, can follow our curiosity to find not too much, not too little, but the information that is “just right”. The researchers also hint at evidence for a spectrum of new curiosity styles beyond the main three, which will surely spark more research in future.

This study also suggests ways Wikipedia (and sites like it) could better support curiosity-driven exploration. For example, rather than suggesting pages based on their popularity or similarity to other pages, Wikipedia could try showing readers their own dynamic knowledge network.

As a Wikipedian would say, this new study is noteworthy. It shows how smaller-scale, exploratory research into people’s reading and browsing can be translated to a much larger scale across languages and cultures.

As AI becomes more influential and the problems of misinformation grow, understanding technologies that shape our access to information – and how we use them – is more important than ever. We know YouTube recommendations can be a radicalising pipeline to extremist content, for example, and ChatGPT is largely indifferent to the truth.

Studying Wikipedia readers reveals a rich picture of people’s freely expressed, diverse online curiosities. It shows an alternative to technologies built on narrower assumptions about what people value, how we learn, and how we want to explore online.![]()

Sarah Polkinghorne, Adjunct Senior Industry Fellow, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

Even in a stubborn cost-of-living crisis, it seems there’s one luxury most Australians won’t sacrifice – their daily cup of coffee.

Coffee sales have largely remained stable, even as financial pressures have bitten over the past few years.

So too have prices. Though many of us became upset when prices began to creep up last year, they’ve since largely settled in the range between $4.00 and $5.50 for a basic drink.

But this could soon have to change. By international standards, Australian coffee prices are low.

No one wants to pay more for essentials, least of all right now. But our independent cafes are struggling.

By not valuing coffee properly, we risk losing the internationally renowned coffee culture we’ve worked so hard to create, and the phenomenal quality of cup we enjoy.

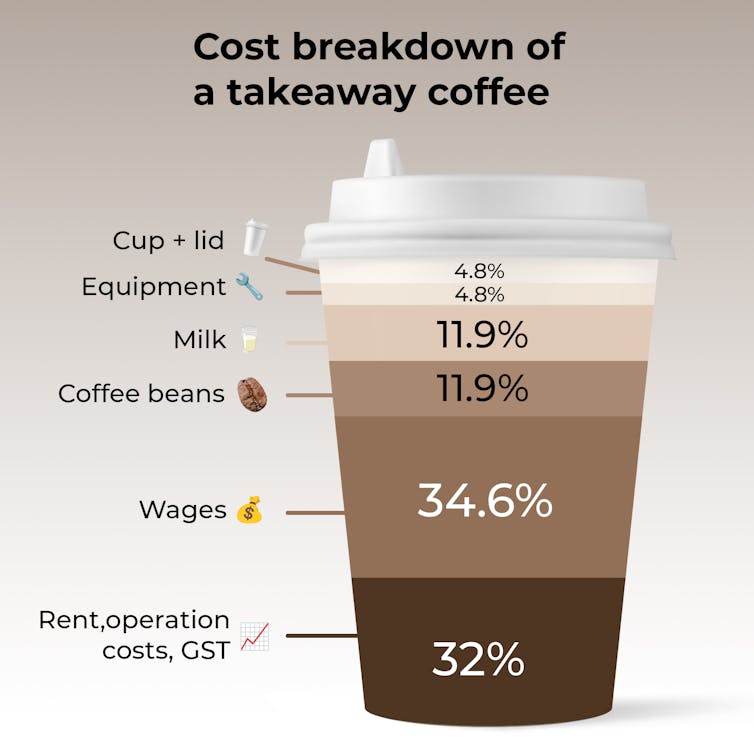

Our recent survey of Australian capital cities found the average price of a small takeaway flat white at speciality venues is A$4.78.

But in some international capitals, it’s almost double this, even after adjusting for local purchasing power parity.

In London, a small flat white costs about A$6.96. Singapore, A$8.42. In Athens, as much as A$9.95.

Over the past few decades, coffee prices haven’t kept pace with input costs. In the early 2000s, after wages, food costs, utilities and rent, many cafes earned healthy profit margins as high as 20%.

The most recent data from IBISWorld show that while Australian cafe net profits have recovered from a drop in 2020, at 7.6%, they remain much lower than the Australian average business profit margin of 13.3%.

For an independent owner operating a cafe with the average turnover of A$300,000, this would amount to a meagre A$22,800 annual net profit after all the bills are paid.

Just looking at the cost of raw inputs – milk, beans, a cup and a lid – might make the margin seem lucrative. But they don’t paint the whole picture.

Over the past few years, renting the building, keeping the lights on and paying staff have all become much bigger factors in the equation for coffee shop owners, and many of these pressures aren’t easing.

1. Green coffee price

Increasingly subject to the effects of climate change, the baseline commodity price of green (unroasted) coffee is going up.

Arabica – the higher quality bean you’re most likely drinking at specialty cafes – is a more expensive raw product. Despite levelling off from post-pandemic highs, its price is still trending up. In 2018, it sold for US$2.93 per kilogram, which is projected to increase to US$4.38 dollars in 2025.

Robusta coffee is cheaper, and is the type typically used to make instant coffee. But serious drought in Vietnam has just pushed the price of robusta to an all-time high, putting pressure on the cost of coffee more broadly.

2. Milk prices

The price of fresh milk has risen by more than 20% over the past two years, and remains at a peak. This has put sustained cost pressure on the production of our most popular drink orders: cappuccinos and flat whites.

3. Wages and utilities

Over the past year, Australian wages have grown at their fastest rate since 2009, which is welcome news for cafe staff, but tough on operators in a sector with low margins.

Electricity prices remain elevated after significant inflation, but could begin to fall mid-year.

One of the key factors keeping prices low in Australia is consumer expectation.

For many people coffee is a fundamental part of everyday life, a marker of livability. Unlike wine or other alcohol, coffee is not considered a luxury or even a treat, where one might expect to pay a little more, or reduce consumption when times are economically tough. We anchor on familiar prices.

Because of this, it really hurts cafe owners to put their prices up. In touch with their customer base almost every day, they’re acutely aware of how much inflation can hurt.

But in Australia, a huge proportion of coffee companies are also passionate about creating a world-class product by only using “specialty coffee”. Ranked at least 80 on a quality scale, specialty beans cost significant more than commodity grade, but their production offers better working conditions for farmers and encourages more sustainable growing practices.

Although not commensurate with the wine industry, there are similarities. Single origin, high quality beans are often sourced from one farm and demand higher prices than commodity grade coffee, where cheaper sourced beans are often combined in a blend.

Running a specialty cafe can also mean roasting your own beans, which requires a big investment in expertise and equipment.

It’s an obvious example of doing the right thing by your suppliers and customers. But specialty cafes face much higher operating costs, and when they’re next to a commodity-grade competitor, customers are typically unwillingly to pay the difference.

When cafe owners put up their prices, we often rush to accuse them of selfishness or profiteering. But they’re often just trying to survive.

Given the quality of our coffee and its global reputation, it shouldn’t surprise us if we’re soon asked to pay a little bit more for our daily brew.

If we are, we should afford the people who create one of our most important “third spaces” kindness and curiosity as to why. ![]()

Emma Felton, Adjunct Senior Researcher, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |