|

| Figure 1 Source: The Conversation (c) 2025 and NSW Government Sharksmart |

|

| Figure 2: Source: The Conversation 2025 |

|

| Figure 3: Source: The Conversation (c) 2025 |

|

| Figure 1 Source: The Conversation (c) 2025 and NSW Government Sharksmart |

|

| Figure 2: Source: The Conversation 2025 |

|

| Figure 3: Source: The Conversation (c) 2025 |

Bushfires are strongly driven by weather: hot, dry and windy conditions can combine to create the perfect environment for flames to spread across the landscape.

But sometimes the relationship flips: fires can generate their own weather systems, which can then dramatically alter the spread and intensity of the blaze.

One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon is the formation of pyrocumulonimbus clouds — towering storm clouds born from fire.

Large bushfires release enormous amounts of energy – sometimes comparable to that emitted from a nuclear bomb. This heats the air in the vicinity of the fire, causing it to rise rapidly in a powerful, buoyant, fire-driven updraft.

Surrounding air rushes in at ground level to replace the rising hot air, feeding the fire with oxygen like a bellows and sometimes accelerating its spread. In extreme cases, the fire and its induced winds can become a self-sustaining system, feeding and growing from the weather it creates.

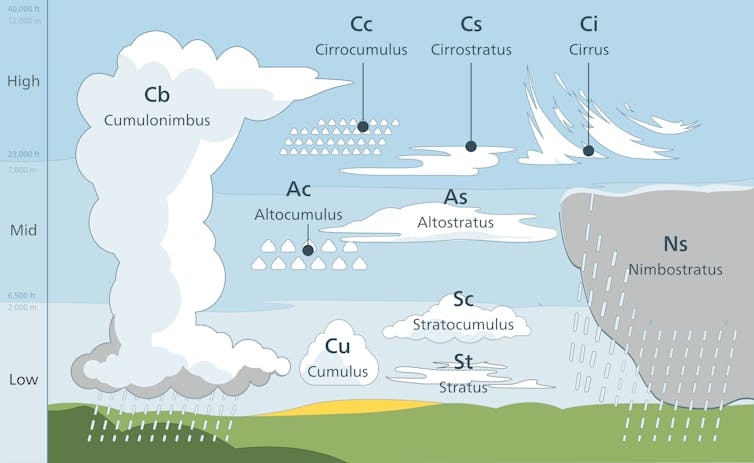

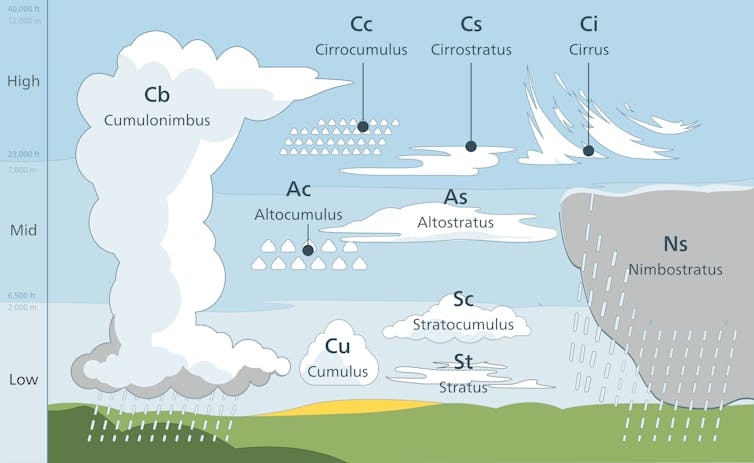

If the plume rises high enough it can cool to a temperature where the water vapour in the plume will begin to condense into clouds. This is essentially the same process that leads to the formation of ordinary cumulus clouds, except it occurs within a fire’s plume and is called pyrocumulus.

If the fire is large and intense enough, the plume can keep rising. As the cloud rises above altitudes of around 3–5 kilometres, temperatures can drop well below freezing. Water droplets freeze into ice crystals, releasing another burst of latent heat that further energises the rising plume.

The rapidly rising plume now contains ice and supercooled water — a mixture that is key to thunderstorm-like processes. It is through this process that a fire-generated thunderstorm is born, a pyrocumulonimbus cloud.

Pyrocumulonimbus clouds can reach altitudes of 10–15 kilometres, penetrating the stratosphere.

Inside them, strong vertical motions generate turbulence, with ice and water droplets colliding and causing the separation of electrical charges. This can result in lightning, often striking far from the original fire front and in some cases igniting new fires.

These clouds can rise so high that they leave a clear signature visible by satellite, including a long shadow cast over the rest of the cloud and smoke. The first pyrocumulonimbus for this summer may have happened yesterday near the border of NSW and Victoria.

Lightning was detected nearby but this was among lightning occurring in many places across the Southeast states, so it may have just been pyrocumulus clouds, which can still present a significant threat. For example, the deadly 2019 Jingellic fire, which produced tornadic winds, developed a towering pyrocumulus but not a pyrocumulonimbus.

The strong updrafts created by pyrocumulonimbus can cause gusty conditions accelerating fire spread and making it less predictable. The storm can produce a strong updraft bringing fresh air in underneath to the fire, while flinging burning embers over 40km potentially creating new fires. At the same time, strong downdrafts created by the storm can flatten trees and create dangerous conditions for firefighters.

Not every bushfire spawns its own weather. Pyrocumulonimbus formation requires a delicate balance between the size and intensity of the fire and the stability of the atmosphere.

Firstly, the fire must be large and intense enough to release massive amounts of heat. Secondly, the surrounding atmosphere needs to be suitably conducive to vertical motion. Both of these together allow for the plume to rise.

Third, moisture in the mid-levels of the atmosphere can enhance the chances of pyrocumulonimbus formation. Moist mid-level air can get caught up in the rising plume and then add to latent heat release when it condenses and freezes, which keeps the plume rising.

Fire-generated thunderstorms were practically unheard of a few decades ago, but they appear to be becoming more common.

One notable example is the unprecedented number that occurred during the Black Summer of 2019–2020. Other outbreaks include around Melbourne in the Black Saturday fires of 2009 and the Canberra fires in 2003.

In all of those cases, the thunderstorms were so intense they injected smoke into stratosphere, where it circled the Earth and affected global climate patterns. Other examples of extreme weather they can cause include fire-generated tornadoes, as well as black hail in the Canberra fires.

Human-caused climate change has already caused more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires for many regions of Australia, including more dangerous conditions for fire-generated thunderstorms.

Observations show more dangerous conditions are now occurring during summer and also with an earlier start to the fire season, particularly in parts of southern and eastern Australia. These trends are very likely to increase into the future, with climate models showing more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires and fire-generated thunderstorms due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Understanding how bushfires can create their own weather is crucial for forecasting and emergency response. Traditional fire behaviour models often assume that weather drives fire, but when fires start driving weather, those models can fail.

Incorporating prediction of fire-generated clouds into fire management systems helps authorities anticipate sudden changes in fire intensity and spread. Targeted research incorporating satellite monitoring and advanced atmospheric modelling is now being used to better understand and detect conditions favourable for pyrocumulonimbus formation.

This knowledge allows for better warnings, resource allocation, and strategies to protect lives and property.

Bushfires are no longer just a local hazard — they can become atmospheric engines with global reach.![]()

Jason Sharples, Professor of Bushfire Dynamics, School of Science, UNSW Canberra, UNSW Sydney; Andrew Dowdy, Principal Research Scientist in Extreme Weather, The University of Melbourne; Luke Burgess, PhD Candidate, Weather and Fire Extremes, The University of Melbourne, and Todd Lane, Professor, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences; ARC Centre of Excellence for the Weather of the 21st Century, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

The Russian - Ukraine war can be best described as a 'drone war' given the advances in technology and tactics that have accured. The guide below provides insight into the variety of drones in use on the battlefield and the advances that have added this lethal new weapon into arsenals.

In the past five years, uncrewed aerial vehicles (drones) have become indispensable in modern warfare. The Russia–Ukraine war has accelerated their ascent: on any given day, there may be hundreds or even thousands of drones operating across the frontlines and behind them.

Cheap, mass-produced consumer technology is the foundation for this growth. Militaries are adapting commercial designs to produce a diverse array of deadly tools.

In sheer numbers, first person view (FPV) drones now dominate the war. Pilots fly them by remote control, sitting in a nearby position and wearing virtual reality goggles to see through the drone’s camera.

FPV drones are very fast, highly manoeuvrable, and often attack by crashing into moving targets and exploding. They are used to strike armoured vehicles, to intercept helicopters and hostile drones, drop anti-personnel mines, and to land near roads and wait to ambush enemy vehicles.

Russia’s main FPV drone is the Molniya-2. Made from plywood, each one can be assembled for less than a thousand dollars using mostly commercial parts, then armed with repurposed mortar or artillery shells.

Russia plans to make two million FPV drones this year.

To avoid radio jamming, Russia has begun controlling these drones via fibre optic cables up to 40 kilometres long. The battlefield is now littered with tens of thousands of very thin fibre optic cables.

FPV drones are also beginning to incorporate artificial intelligence (AI) – at first to assist pilots, and later for greater autonomy.

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) has so far only engaged with FPV drones by racing commercial devices in multinational competitions.

Multicopters are more general-purpose and easier to operate than FPV drones. They can be used for battlefield reconnaissance, intercepting hostile drones, electronic warfare, GPS jamming, communications relay, delivering packages and dropping small mines or bombs. Many are commercial drones modified with different kits for different missions.

Russia commonly uses small hobbyist quadcopters such as the Chinese-made DJI Mavic 3, the DJI Matrice and the Autel EVO II.

There are also larger purpose-built machines, such as the MiS-150 quadcopter and MiS-35 hexacopter, which can carry payloads up to 15 kilograms. The in-development Buran hexacopter can carry a whopping 80kg.

The ADF operates the R70 Sky Ranger quadcopter for airbase surveillance and defence tasks.

Winged drones come in two broad groups: one-way (kamikaze or loitering) and reusable.

One‑way drones are used for long‑range strikes against cities, transport and infrastructure. Russia mainly uses the Geran series, which it manufactures in a giant factory 1,000km east of Moscow from designs based on Iran’s Shahed drones.

The medium-sized Geran is most common, used for long-range strikes against Ukrainian cities, transport networks, and civilian and military infrastructure.

By late June 2025, Russia had fired some 29,000 Gerans, and it can now make 2,700 more each month. Simplified versions with no warhead are also used as decoys to distract air defences – not only in Ukraine, but also in Poland and Romania.

The main reusable drones are the Orlan-10 and the ZALA 421. These provide battlespace surveillance and help coordinate artillery and FPV drone strikes on Ukrainian targets.

Orlan-10s are now being also used as motherships carrying and launching smaller FPV drones.

Another reusable drone is the ZALA Lancet, used for both reconnaissance and strike missions. It is a so-called “loitering munition”: it can be launched, stay in the air for some time, identify targets with an onboard camera, and then attack if its human operator commands. More sophisticated than FPV drones, these are also far more expensive.

The ADF operates several reconnaissance drones similar to the Orlan-10: the Shadow Tactical, Wasp AE and Puma AE.

The ADF has also recently purchased some loitering munitions: the Switchblade 300 and OWL.

The ADF also operates the very large Triton maritime surveillance drone, which has no Russian equivalent, and is developing the Ghost Bat, a high-speed drone able to assist fast jet fighter and strike aircraft.

Counter-drone technology is in high demand. However, drones are small, fast and numerous, which makes it inherently difficult to defend against them in a comprehensive way.

Counter-drone systems include combinations of warning sensors, backpack and vehicle-mounted electronic jammers, gun systems, surface-to-air missiles, laser devices and electromagnetic pulse systems.

FPV and multicopter drones are too small for fighter aircraft to counter them. However, larger aircraft-like drones are more vulnerable. New air-launched rocket systems now allow fighters to shoot down a dozen Gerans during each sortie.

As drones become even more widespread and diverse, the balance between cheap mass-produced attack platforms and effective, adaptable defences will shape the conflicts of the future.

Molniya: Militaer Aktuell;

Fibre optic drone: АрміяІнформ/Wikimedia;

MiS-150: Lamp of Knowledge/YouTube;

MiS-35: United24 Media;

R70-skyranger: ELP;

Geran-2: Scott Peterson/Getty Images;

Orlan-10: Mike1979 Russia/Wikimedia;

Zala 421: Airforce Technology/JSC Concern;

Zala lancet 3: Vitaly V Kuzmin;

Puma-3-AE: Naval Technology/Business Wire;

Wasp-AE: Sgt. Janine Fabre, Australian Defence. Infographics: Matt Garrow/The Conversation.![]()

Matt Garrow, Editorial Web Developer, The Conversation and Michael Lucy, Science Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As a scholar researching clouds, I have spent much of my time trying to understand the economy of the sky. Not the weather reports showing scudding rainclouds, but the deeper logic of cloud movements, their distributions and densities and the way they intervene in light, regulate temperatures and choreograph heat flows across our restless planet.

Recently, I have been noticing something strange: skies that feel hollowed out, clouds that look like they have lost their conviction. I think of them as ghost clouds. Not quite absent, but not fully there. These wispy formations drift unmoored from the systems that once gave them coherence. Too thin to reflect sunlight, too fragmented to produce rain, too sluggish to stir up wind, they give the illusion of a cloud without its function.

We think of clouds as insubstantial. But they matter far beyond their weight or tangibility. In dry Western Australia where I live, rain-bringing clouds are eagerly anticipated. But the winter storms which bring most rain to the south-west are being pushed south, depositing vital fresh water into the oceans. More and more days pass under a hard, endless blue – beautiful, but also brutal in its vacancy.

Worldwide, cloud patterns are now changing in concerning ways. Scientists have found the expanse of Earth’s highly reflective clouds is steadily shrinking. With less heat reflected, the Earth is now trapping more heat than expected.

When there are fewer and fewer clouds, it doesn’t make headlines as floods or fires do. Their absence is quiet, cumulative and very worrying.

To be clear, clouds aren’t going to disappear. They may increase in some areas. But the belts of shiny white clouds we need most are declining between 1.5 and 3% per decade.

These clouds are the best at reflecting sunlight back to space, especially in the sunniest parts of the world close to the equator. By contrast, broken grey clouds reflect less heat, while less light hits polar regions, giving polar clouds less to reflect.

Clouds are often thought of as an ambient backdrop to climate action. But we’re now learning this is a fundamental oversight. Clouds aren’t décor – they’re dynamic, distributed and deeply consequential infrastructure able to cool the planet and shape the rainfall patterns seeding life below. These masses of tiny water droplets or ice crystals represent climate protection accessible to all, regardless of nation, wealth or politics.

On average, clouds cover two-thirds of the Earth’s surface, clustering over the oceans. Of all solar radiation reflected back to space, clouds are responsible for about 70%.

Clouds mediate extremes, soften sunlight, ferry moisture and form invisible feedback loops sustaining a stable climate.

If clouds become rarer or leave, it’s not just a loss to the climate system. It’s a loss to how we perceive the world.

When glaciers melt, species die out or coral reefs bleach and die, traces are often left of what was there. But if cloud cover diminishes, it leaves only an emptiness that’s hard to name and harder still to grieve. We have had to learn how to grieve other environmental losses. But we do not yet have a way to mourn the way skies used to be.

And yet we must. To confront loss on this scale, we must allow ourselves to mourn – not out of despair, but out of clarity. Grieving the atmosphere as it used to be is not weakness. It is planetary attention, a necessary pause that opens space for care and creative reimagination of how we live with – and within – the sky.

For generations, Australia’s First Nations have read the clouds and sky, interpreting their forms to guide seasonal activities. The Emu in the Sky (Gugurmin in Wiradjuri) can be seen in the Milky Way’s dark dust. When the emu figure is high in the night sky, it’s the right time to gather emu eggs.

The skies are changing faster than our systems of understanding can keep up.

One solution is to reframe how we perceive weather phenomena such as clouds. As researchers in Japan have observed, weather is a type of public good – a “weather commons”. If we see clouds not as leftovers from an unchanging past, but as invitations to imagine new futures for our planet, we might begin to learn how to live more wisely and attentively with the sky.

This might mean teaching people how to read the clouds again – to notice their presence, their changes, their disappearances. We can learn to distinguish between clouds which cool and those which drift, decorative but functionally inert. Our natural affinity to clouds makes them ideal for engaging citizens.

To read clouds is to understand where they formed, what they carry and whether they might return tomorrow. From the ground, we can see whether clouds have begun a slow retreat from the places that need them most.

For millennia, humans have treated weather as something beyond our control, something that happens to us. But our effects on Earth have ballooned to the point that we are now helping shape the weather, whether by removing forests which can produce much of their own rain or by funnelling billions of tonnes of fossil carbon into the atmosphere. What we do below shapes what happens above.

We are living through a very brief window in which every change will have very long term consequences. If emissions continue apace, the extra heating will last millennia.

I propose cloud literacy not as solution, but as a way to urgently draw our attention to the very real change happening around us.

We must move from reaction to atmospheric co-design – not as technical fix, but as a civic, collective and imaginative responsibility.

Professor Christian Jakob provided feedback and contributed to this article, while Dr Jo Pollitt and Professor Helena Grehan offered comments and edits.![]()

Rumen Rachev, PhD Candidate, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.