When bushfires make their own weather

Bushfires are strongly driven by weather: hot, dry and windy conditions can combine to create the perfect environment for flames to spread across the landscape.

But sometimes the relationship flips: fires can generate their own weather systems, which can then dramatically alter the spread and intensity of the blaze.

One of the most striking examples of this phenomenon is the formation of pyrocumulonimbus clouds — towering storm clouds born from fire.

How can a fire make winds and clouds?

Large bushfires release enormous amounts of energy – sometimes comparable to that emitted from a nuclear bomb. This heats the air in the vicinity of the fire, causing it to rise rapidly in a powerful, buoyant, fire-driven updraft.

Surrounding air rushes in at ground level to replace the rising hot air, feeding the fire with oxygen like a bellows and sometimes accelerating its spread. In extreme cases, the fire and its induced winds can become a self-sustaining system, feeding and growing from the weather it creates.

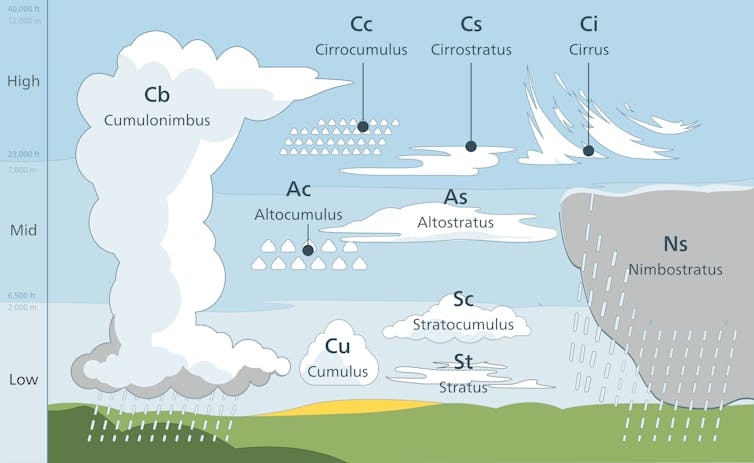

If the plume rises high enough it can cool to a temperature where the water vapour in the plume will begin to condense into clouds. This is essentially the same process that leads to the formation of ordinary cumulus clouds, except it occurs within a fire’s plume and is called pyrocumulus.

Fire-generated thunderstorms

If the fire is large and intense enough, the plume can keep rising. As the cloud rises above altitudes of around 3–5 kilometres, temperatures can drop well below freezing. Water droplets freeze into ice crystals, releasing another burst of latent heat that further energises the rising plume.

The rapidly rising plume now contains ice and supercooled water — a mixture that is key to thunderstorm-like processes. It is through this process that a fire-generated thunderstorm is born, a pyrocumulonimbus cloud.

Pyrocumulonimbus clouds can reach altitudes of 10–15 kilometres, penetrating the stratosphere.

Inside them, strong vertical motions generate turbulence, with ice and water droplets colliding and causing the separation of electrical charges. This can result in lightning, often striking far from the original fire front and in some cases igniting new fires.

These clouds can rise so high that they leave a clear signature visible by satellite, including a long shadow cast over the rest of the cloud and smoke. The first pyrocumulonimbus for this summer may have happened yesterday near the border of NSW and Victoria.

Lightning was detected nearby but this was among lightning occurring in many places across the Southeast states, so it may have just been pyrocumulus clouds, which can still present a significant threat. For example, the deadly 2019 Jingellic fire, which produced tornadic winds, developed a towering pyrocumulus but not a pyrocumulonimbus.

The strong updrafts created by pyrocumulonimbus can cause gusty conditions accelerating fire spread and making it less predictable. The storm can produce a strong updraft bringing fresh air in underneath to the fire, while flinging burning embers over 40km potentially creating new fires. At the same time, strong downdrafts created by the storm can flatten trees and create dangerous conditions for firefighters.

When does this happen?

Not every bushfire spawns its own weather. Pyrocumulonimbus formation requires a delicate balance between the size and intensity of the fire and the stability of the atmosphere.

Firstly, the fire must be large and intense enough to release massive amounts of heat. Secondly, the surrounding atmosphere needs to be suitably conducive to vertical motion. Both of these together allow for the plume to rise.

Third, moisture in the mid-levels of the atmosphere can enhance the chances of pyrocumulonimbus formation. Moist mid-level air can get caught up in the rising plume and then add to latent heat release when it condenses and freezes, which keeps the plume rising.

The future of fire and thunder

Fire-generated thunderstorms were practically unheard of a few decades ago, but they appear to be becoming more common.

One notable example is the unprecedented number that occurred during the Black Summer of 2019–2020. Other outbreaks include around Melbourne in the Black Saturday fires of 2009 and the Canberra fires in 2003.

In all of those cases, the thunderstorms were so intense they injected smoke into stratosphere, where it circled the Earth and affected global climate patterns. Other examples of extreme weather they can cause include fire-generated tornadoes, as well as black hail in the Canberra fires.

Human-caused climate change has already caused more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires for many regions of Australia, including more dangerous conditions for fire-generated thunderstorms.

Observations show more dangerous conditions are now occurring during summer and also with an earlier start to the fire season, particularly in parts of southern and eastern Australia. These trends are very likely to increase into the future, with climate models showing more dangerous weather conditions for bushfires and fire-generated thunderstorms due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Why understanding this matters

Understanding how bushfires can create their own weather is crucial for forecasting and emergency response. Traditional fire behaviour models often assume that weather drives fire, but when fires start driving weather, those models can fail.

Incorporating prediction of fire-generated clouds into fire management systems helps authorities anticipate sudden changes in fire intensity and spread. Targeted research incorporating satellite monitoring and advanced atmospheric modelling is now being used to better understand and detect conditions favourable for pyrocumulonimbus formation.

This knowledge allows for better warnings, resource allocation, and strategies to protect lives and property.

Bushfires are no longer just a local hazard — they can become atmospheric engines with global reach.![]()

Jason Sharples, Professor of Bushfire Dynamics, School of Science, UNSW Canberra, UNSW Sydney; Andrew Dowdy, Principal Research Scientist in Extreme Weather, The University of Melbourne; Luke Burgess, PhD Candidate, Weather and Fire Extremes, The University of Melbourne, and Todd Lane, Professor, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences; ARC Centre of Excellence for the Weather of the 21st Century, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.