This year’s climate talks saw real progress – just not on fossil fuels

It wasn’t a comfortable process for the tens of thousands of delegates trying to hash out progress on climate change on the edge of the Amazon in Belém, Brazil. I experienced the challenges of the United Nations COP30 climate talks firsthand.

Delegates were hot and sweaty. Tech and aircon didn’t always work. Both flood and fire disrupted negotiations over the fortnight of negotiations. It drove home how climate change feels. But despite the discomfort, some progress was made.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva dubbed it the “COP of Truth”. Delegates did not shy away from the urgency of the moment as climate change intensifies and emissions continue to climb.

Ahead of the talks, many feared global political headwinds and the United States’ departure from the Paris Agreement would undermine this year’s talks. The fact that nearly 60,000 delegates attended these talks – the second highest ever – shows this isn’t the case.

Progress was made on funding climate finance and adaptation to the changes already emerging. But efforts on ending reliance on fossil fuels faltered in the face of strong resistance by fossil fuel powers. Much progress in Belém happened outside the main talks.

So what did COP30 deliver?

At one stage it looked like COP30 might crack the hardest nut in climate policy – reaching agreement on phasing out fossil fuels. Nations agreed two years ago that it was necessary to move away from fossil fuels. But no plan had yet been devised to get there.

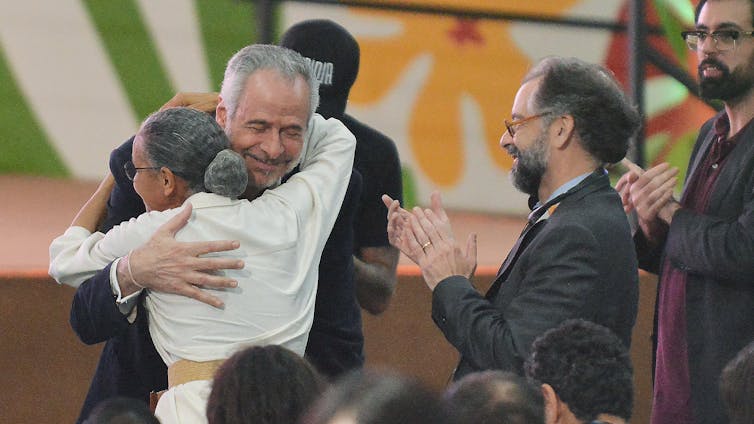

Brazil had a plan: build support for a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, championed by President Lula and pushed strongly by Environment Minister Marina Silva. It drew support from more than 80 countries, including major fossil fuel exporters such as Norway and Australia. Anticipating pushback, Brazil worked to boost support outside the main talks before bringing the plan in.

It didn’t work. By the end of COP30, all mention of a fossil fuel roadmap had been scrubbed from the text of the final outcomes, following fierce pushback from countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and India and many emerging economies.

Instead, countries agreed to launch “the Global Implementation Accelerator […] to keep 1.5°C within reach” and “taking into account” previous COP decisions. This initiative will be shepherded by the Brazilian COP30 Presidency and the leaders of next year’s COP31 talks, Turkey and Australia.

President Lula vowed to continue advocating for a fossil fuel roadmap at the G20. Colombia and the Netherlands will hold a conference on fossil fuel phaseout in April 2026. The COP30 decision text also makes reference to a “high-level event in 2026” which could take place in the Pacific. Without blockers of consensus at these meetings, a coalition of willing countries could make real progress in setting timelines and exchanging policy ideas for fossil fuel phase-out.

The decision to develop a just transition mechanism was welcomed as a win for workers and communities. The new mechanism’s purpose will be to increase international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building and knowledge-sharing as countries shift towards a low carbon global economy.

Efforts to boost financing for climate adaptation bogged down, reflecting the trade-offs over fossil fuels.

These funds are meant to help nations most exposed to severe climate damage, usually poorer and with low emissions. These nations led the charge for a tripling of climate finance by 2030 from the US$40 billion (A$62 billion) agreed at COP26 four years ago. But the agreed text merely “calls for efforts to at least triple adaptation finance by 2035”, which pushes out the timeframe and has no funding baseline.

Funding for tropical forests

One of Brazil’s own initiatives, the Tropical Forest Facility, achieved greater success, securing US$9.5 billion (A$14.7 billion) in funding pledges – a COP record.

The trust fund for rainforests is designed to provide resources to arrest global deforestation and protect Indigenous lands, including in the Amazon’s vital carbon sink.

Support for a roadmap towards ending deforestation secured 92 backers.

The success of these deforestation initiatives points to the effectiveness of the COP’s Action Agenda, aimed at spurring on climate action outside formal negotiations and including commitments from business, investors and civil society. As formal negotiations bog down, these bypasses may end up replacing negotiations in driving progress.

American absence

Ahead of COP30, analysts feared the ongoing attacks on climate action by the Trump administration would undermine the international negotiations.

COP30 was the first climate summit without a US government delegation. At first, the absence came as a relief.

But by summit’s end, the disappearance of the world’s biggest historical emitter and largest economy from negotiations had taken its toll.

Developing countries from the African group of negotiators argued better metrics and plans would be meaningless without funding to implement them. Traditionally, the US has been a major funder. No longer.

The US decision to turn its back on climate action created a subdued atmosphere. New finance pledges were broadly underwhelming, likely due to the dampening effect of the US retreat.

Early on, many hoped renewables and clean tech giant China might fill the leadership void. China’s clean tech exports last year were enough to cut overseas emissions by 1%. The huge industrial power produces almost 32% of the world’s carbon emissions. These emissions have plateaued, in turn suggesting global emissions may now have peaked.

But China showed reluctance to take up the mantle, preferring to remain focused on its own domestic energy transition. Chinese negotiators spent most of their energy pushing back against new European trade measures targeting emissions-intensive production.

It was left to some of the smallest nations, Indigenous peoples and civil society to lead calls for sticking to the science, ramping up urgency and accelerating the rollout of solutions. An estimated 70,000 people marched in the streets of Belém, staging a mock funeral for fossil fuels. It was an important affirmation of widespread public support for climate action.

What legacy?

As the UN’s climate Executive Secretary Simon Stiell said midway through COP30, nations had to “give a little to get a lot”.

Many countries will be reflecting they gave a lot but got very little. The biggest winners were, yet again, the world’s petrostates who successfully frustrated attempts to address fossil fuels.

Questions will inevitably be asked over whether these consensus-based talks are fit for purpose, given they can be gamed by blockers.

For many, COP30 will be regarded as a failure on fossil fuels and addressing major gaps between national pledges to cut emissions and what’s needed to hold warming to 1.5°C.

This is true. But another view would be that these talks made real progress on important areas despite considerable challenges.

Negotiators from 194 countries showed up and continued to talk and work together to tackle the worsening crisis. Nearly half of those countries have shown they’re ready to begin weaning themselves off fossil fuels through their support for the phase-out roadmap. They don’t have to wait for a UN consensus to act. Fossil fuel exporters only have power while other nations buy and rely on their products.

The world’s climate talks are now clearly moving away from arcane negotiations to the pressing real-world challenges of doing the work. In a rapidly warming world, all issues are becoming climate issues.![]()

Jacqueline Peel, Professor of Law, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.