|

photo: the Australian Light Horse camp at Belah, Palestine, 1918 |

|

| Photo: an Australian Machine Gun Battalion, England, Aug 1940 |

|

| Photo: the 2nd AIF marches past in Sydney, January 1940 |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

Even in a stubborn cost-of-living crisis, it seems there’s one luxury most Australians won’t sacrifice – their daily cup of coffee.

Coffee sales have largely remained stable, even as financial pressures have bitten over the past few years.

So too have prices. Though many of us became upset when prices began to creep up last year, they’ve since largely settled in the range between $4.00 and $5.50 for a basic drink.

But this could soon have to change. By international standards, Australian coffee prices are low.

No one wants to pay more for essentials, least of all right now. But our independent cafes are struggling.

By not valuing coffee properly, we risk losing the internationally renowned coffee culture we’ve worked so hard to create, and the phenomenal quality of cup we enjoy.

Our recent survey of Australian capital cities found the average price of a small takeaway flat white at speciality venues is A$4.78.

But in some international capitals, it’s almost double this, even after adjusting for local purchasing power parity.

In London, a small flat white costs about A$6.96. Singapore, A$8.42. In Athens, as much as A$9.95.

Over the past few decades, coffee prices haven’t kept pace with input costs. In the early 2000s, after wages, food costs, utilities and rent, many cafes earned healthy profit margins as high as 20%.

The most recent data from IBISWorld show that while Australian cafe net profits have recovered from a drop in 2020, at 7.6%, they remain much lower than the Australian average business profit margin of 13.3%.

For an independent owner operating a cafe with the average turnover of A$300,000, this would amount to a meagre A$22,800 annual net profit after all the bills are paid.

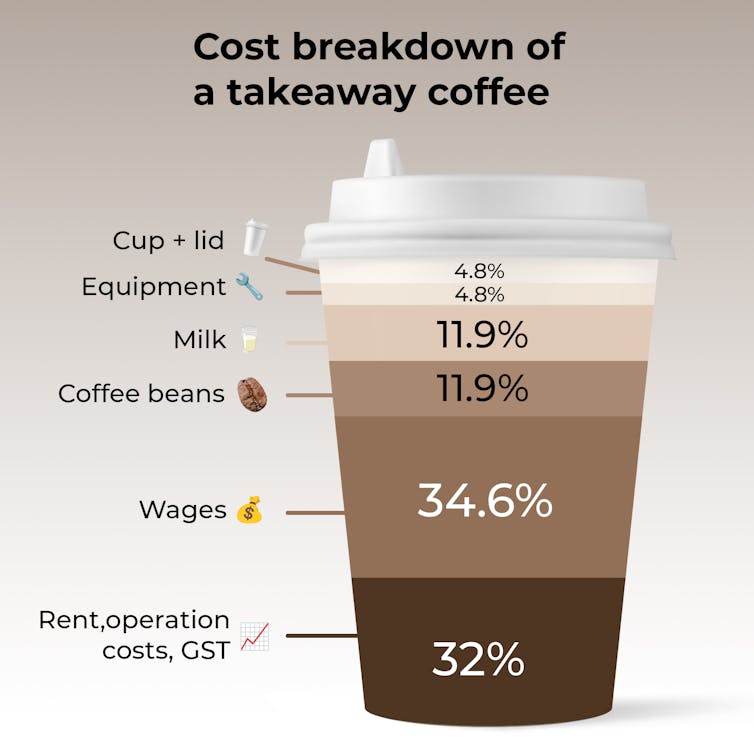

Just looking at the cost of raw inputs – milk, beans, a cup and a lid – might make the margin seem lucrative. But they don’t paint the whole picture.

Over the past few years, renting the building, keeping the lights on and paying staff have all become much bigger factors in the equation for coffee shop owners, and many of these pressures aren’t easing.

1. Green coffee price

Increasingly subject to the effects of climate change, the baseline commodity price of green (unroasted) coffee is going up.

Arabica – the higher quality bean you’re most likely drinking at specialty cafes – is a more expensive raw product. Despite levelling off from post-pandemic highs, its price is still trending up. In 2018, it sold for US$2.93 per kilogram, which is projected to increase to US$4.38 dollars in 2025.

Robusta coffee is cheaper, and is the type typically used to make instant coffee. But serious drought in Vietnam has just pushed the price of robusta to an all-time high, putting pressure on the cost of coffee more broadly.

2. Milk prices

The price of fresh milk has risen by more than 20% over the past two years, and remains at a peak. This has put sustained cost pressure on the production of our most popular drink orders: cappuccinos and flat whites.

3. Wages and utilities

Over the past year, Australian wages have grown at their fastest rate since 2009, which is welcome news for cafe staff, but tough on operators in a sector with low margins.

Electricity prices remain elevated after significant inflation, but could begin to fall mid-year.

One of the key factors keeping prices low in Australia is consumer expectation.

For many people coffee is a fundamental part of everyday life, a marker of livability. Unlike wine or other alcohol, coffee is not considered a luxury or even a treat, where one might expect to pay a little more, or reduce consumption when times are economically tough. We anchor on familiar prices.

Because of this, it really hurts cafe owners to put their prices up. In touch with their customer base almost every day, they’re acutely aware of how much inflation can hurt.

But in Australia, a huge proportion of coffee companies are also passionate about creating a world-class product by only using “specialty coffee”. Ranked at least 80 on a quality scale, specialty beans cost significant more than commodity grade, but their production offers better working conditions for farmers and encourages more sustainable growing practices.

Although not commensurate with the wine industry, there are similarities. Single origin, high quality beans are often sourced from one farm and demand higher prices than commodity grade coffee, where cheaper sourced beans are often combined in a blend.

Running a specialty cafe can also mean roasting your own beans, which requires a big investment in expertise and equipment.

It’s an obvious example of doing the right thing by your suppliers and customers. But specialty cafes face much higher operating costs, and when they’re next to a commodity-grade competitor, customers are typically unwillingly to pay the difference.

When cafe owners put up their prices, we often rush to accuse them of selfishness or profiteering. But they’re often just trying to survive.

Given the quality of our coffee and its global reputation, it shouldn’t surprise us if we’re soon asked to pay a little bit more for our daily brew.

If we are, we should afford the people who create one of our most important “third spaces” kindness and curiosity as to why. ![]()

Emma Felton, Adjunct Senior Researcher, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The United Nations Environment Assembly this week considered a resolution on solar radiation modification, which refers to controversial technologies intended to mask the heating effect of greenhouse gases by reflecting some sunlight back to space.

Proponents argue the technologies will limit the effects of climate change. In reality, this type of “geoengineering” risks further destabilising an already deeply disturbed climate system. What’s more, its full impacts cannot be known until after deployment.

The draft resolution initially called for the convening of an expert group to examine the benefits and risks of solar radiation modification. The motion was withdrawn on Thursday after no consensus could be reached on the controversial topic.

A notable development was a call from some Global South countries for “non-use” of solar radiation modification. We strongly support this position. Human-caused climate change is already one planetary-scale experiment too many – we don’t need another.

In some circles, solar geoengineering is gaining prominence as a response to the climate crisis. However, research has consistently identified potential risks posed by the technologies such as:

unpredictable effects on climate and weather patterns

biodiversity loss, especially if use of the technology was halted abruptly

undermining food security by, for example, reducing light and increasing salinity on land

the infringement of human rights across generations – including, but not limited to, passing on huge risks to generations that will come after us.

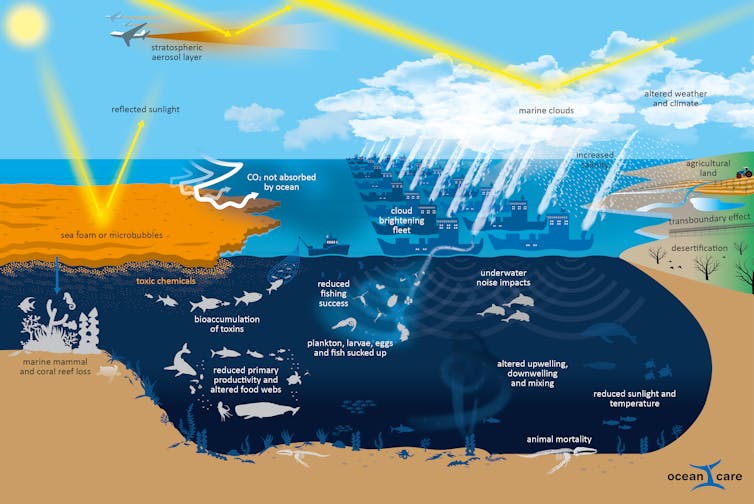

Here, we discuss several examples of solar radiation modification which exemplify the threats posed by these technologies. These are also depicted in the graphic below.

In April 2022, an American startup company released two weather balloons into the air from Mexico. The experiment was conducted without approval from Mexican authorities.

The intent was to cool the atmosphere by deflecting sunlight. The resulting reduction in warming would be sold for profit as “cooling credits” to those wanting to offset greenhouse gas pollution.

Appreciably cooling the climate would, in reality, require injecting millions of metric tons of aerosols into the stratosphere, using a purpose-built fleet of high-altitude aircraft. Such an undertaking would alter global wind and rainfall patterns, leading to more drought and cyclones, exacerbating acid rainfall and slowing ozone recovery.

Once started, this stratospheric aerosol injection would need to be carried out continually for at least a century to achieve the desired cooling effect. Stopping prematurely would lead to an unprecedented rise in global temperatures far outpacing extreme climate change scenarios.

Another solar geoengineering technology, known as marine cloud brightening, seeks to make low-lying clouds more reflective by spraying microscopic seawater droplets into the air. Since 2017, trials have been underway on the Great Barrier Reef.

The project is tiny in scale, and involves pumping seawater onto a boat and spraying it from nozzles towards the sky. The project leader says the mist-generating machine would need to be scaled up by a factor of ten, to about 3,000 nozzles, to brighten nearby clouds by 30%.

After years of trials, the project has not yet produced peer-reviewed empirical evidence that cloud brightening could reduce sea surface temperatures or protect corals from bleaching.

The Great Barrier Reef is the size of Italy. Scaling up attempts at cloud brightening would require up to 1,000 machines on boats, all pumping and spraying vast amounts of seawater for months during summer. Even if it worked, the operation is hardly, as its proponents claim, “environmentally benign”.

The technology’s effects remain unclear. For the Great Barrier Reef, less sunlight and lower temperatures could alter water movement and mixing, harming marine life. Marine life may also be killed by pumps or negatively affected by the additional noise pollution. And on land, marine cloud brightening may lead to altered rainfall patterns and increased salinity, damaging agriculture.

More broadly, 101 governments last year agreed to a statement describing marine-based geoengineering, including cloud brightening, as having “the potential for deleterious effects that are widespread, long-lasting or severe”.

The Arctic Ice Project involves spreading a layer of tiny glass spheres over large regions of sea ice to brighten its surface and halt ice loss.

Trials have been conducted on frozen lakes in North America. Scientists recently showed the spheres actually absorb some sunlight, speeding up sea-ice loss in some conditions.

Another proposed intervention is spraying the ocean with microbubbles or sea foam to make the surface more reflective. This would introduce large concentrations of chemicals to stabilise bubbles or foam at the sea surface, posing significant risk to marine life, ecosystem function and fisheries.

Some scientists investigating solar geoengineering discuss the need for “exit ramps” – the termination of research once a proposed intervention is deemed to be technically infeasible, too risky or socially unacceptable. We believe this point has already been reached.

Since 2022, more than 500 scientists from 61 countries have signed an open letter calling for an international non-use agreement on solar geoengineering. Aside from the types of risks discussed above, the letter said the speculative technologies detract from the urgent need to cut global emissions, and that no global governance system exists to fairly and effectively regulate their deployment.

Calls for outdoor experimentation of the technologies are misguided and detract energy and resources from what we need to do today: phase out fossil fuels and accelerate a just transition worldwide.

Climate change is the greatest challenge facing humanity, and global responses have been woefully inadequate. Humanity must not pursue dangerous distractions that do nothing to tackle the root causes of climate change, come with incalculable risk, and will likely further delay climate action.![]()

James Kerry, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, James Cook University, Australia and Senior Marine and Climate Scientist, OceanCare, Switzerland, James Cook University; Aarti Gupta, Professor of Global Environmental Governance, Wageningen University, and Terry Hughes, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.