What we know about Australia’s arms exports: we’ve analysed the data

Thousands of protesters have been out in force in Melbourne this week to disrupt the Land Forces International Land Defence Exposition, where defence companies from around the world are showcasing their latest designs in weapons and technology.

The activists are protesting the use of such weapons – in particular, allegations of use against Palestinian civilians by Israeli forces in Gaza.

With the expo in Melbourne this week, there is also renewed attention on Australia’s weapons exports and imports. So, how much do we know about where Australia is sending its arms, and how many arms it is importing?

What gets reported?

The government limits what information is made publicly available about arms exports and imports due to both security and commercial reasons.

Australian exports include both military-specific and dual-use goods and technologies, such as computer components used in weapons. There is a strict export control system that is intended to prevent weapons from getting into the hands of our adversaries and to ensure they meet our obligations under international law.

But this system has been criticised for being opaque. This is because Australia only publicly reports recipient countries for items it is obliged to disclose under the Arms Trade Treaty, or in some cases, during parliamentary hearings or other similar processes.

Separately, Australia’s Defence Export Office publishes quarterly reports with very basic information, such as the number and types of export applications it receives and the total value of permits it issues. It only specifies the export permits for “end users” by continent, not country.

In the year 2023–24, the office finalised more than 4,000 export defence permits, with the value of permits issued exceeding an estimated A$100 billion.

Unlike other countries, Australia does not specify exactly what types of goods it has approved for import or export.

The government also does not report how many issued permits are actually used by companies to trade goods. The movement of military goods to and from Australia is tracked through other processes, such as customs controls.

Finally, requests for further information are typically met with resistance from the government, on the basis such disclosures would breach security or commercial confidentiality arrangements.

However, while not authoritative, information about Australian exports can be pieced together from a variety of sources. This includes reports from exporting companies themselves, reports sent by exporters to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and statements made in parliament and in other government reporting.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) also tracks arms shipments between countries by assessing public information. Some countries provide information directly to their analysts.

Here is some data we have compiled from SIPRI showing Australia’s exports and imports for the most recent five-year period from 2019–23, based on what is publicly known.

Australia’s arms exports

According to SIPRI, Australia ranked 13th in overall military expenditures globally in 2022–23, spending US$32.3 billion (A$49 billion), or about 1.9% of GDP.

Australia was also one of the top 20 arms exporters in the world from 2019–23, though its share of total global arms exports was just 0.6%, similar to Canada. This share was up from 0.3% in 2014–18.

The United States, meanwhile, accounted for 42% of global arms exports in 2019–23.

The map below shows the top recipients for Australian arms during this five-year period. The top three recipients were Canada (32% of Australia’s total exports), Chile (28%) and the United States (11%).

What do we know about Israel?

According to SIPRI, Israel’s arms imports for 2019–23 came primarily from the US (69%) and Germany (30%).

The Albanese government maintains Australia hasn’t supplied weapons or ammunition to Israel in the past five years. This week, it also explicitly backed the United Kingdom’s decision to curb arms exports to Israel.

Some of what we know about Australia’s exports to Israel has been the result of questions being put to parliamentarians.

In June, the government said it had granted eight permits to export defence-related equipment to Israel since the Gaza war began last October. It clarified that most of the items were being sent to Israel for repair and then returned to Australian defence and law enforcement for their use.

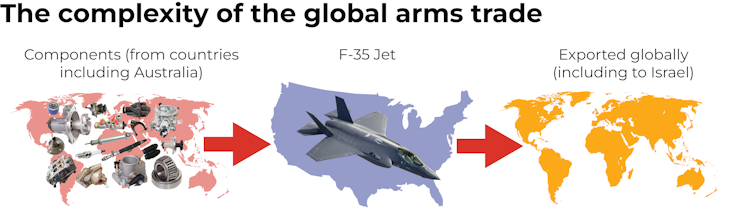

This reporting, however, does not capture sub-components that are manufactured in Australia and sent to a central repository overseas to be used in a larger platform, like an F-35 jet, which can then be sent to Israel from the US or Europe.

What do we know about Ukraine?

In the case of Ukraine, Australia has exported conventional arms such as Bushmaster armoured vehicles and artillery. Some of these have been included in its public reporting, given the type of equipment being provided.

According to SIPRI, the largest sources of military goods to Ukraine have been the US, Germany and Poland.

Australia’s arms imports

SIPRI’s data shows that Australia was eighth-largest importer of arms from 2019–23, accounting for 3.7% of global arms imports.

The vast majority (80%) of its imports during this period came from the United States, followed by Spain at 15%.

The types of items that Australia has reported importing from the US include ships, aircraft, helicopters and missile defence systems. In addition, SIPRI noted that Australia ordered 300 long-range missiles from the US in 2023.

However, because it often takes years for these large defence items to be built, quite often there is a lag in the reporting of import data.

For example, Australia’s recently announced deal with Hanwha, a Korean defence company, to build artillery and armoured vehicles will not be featured in these statistics as some components of the vehicles and artillery will be built in a factory in Geelong, Australia, while others will not be delivered in this reporting period.

Also, while export control measures deal with goods that are built elsewhere and brought to Australia, some permits are required to import the know-how to build controlled defence goods in Australia. This is another reason imports like these might not appear on public reports.![]()

Lauren Sanders, Senior Research Fellow on Law and the Future of War, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are very welcome but are subject to moderation.