| Sample 1 - AI created avatar - female |

| Sample 2 -AI created avatar - male |

| Sample 1 - AI created avatar - female |

| Sample 2 -AI created avatar - male |

|

| Shutterstock |

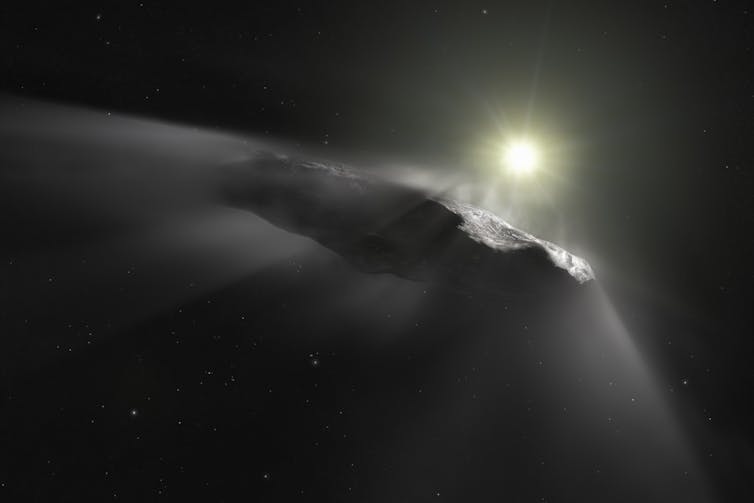

In 2017, NASA discovered and later confirmed the first interstellar object to enter our Solar System.

It wasn’t aliens. But artist impressions of the object (called ‘Oumuamua, the Hawaiian word for “scout”) do resemble an alien spaceship out of a sci-fi novel. This strange depiction is because astronomers don’t quite know how to classify the interstellar visitor.

Its speed and path around the Sun don’t match a typical asteroid, but it also has no bright tail or nucleus (icy core) we normally associate with comets. However, 'Oumuamua has erratic motions that are consistent with gas escaping from its surface. This “dark comet” has had astronomers scratching their heads ever since.

Flash forward to today, and more of these mysterious objects have been discovered, with another ten announced just last week. While their nature and origins remain elusive, astronomers recently confirmed dark comets fall into two main categories: smaller objects that reside in our inner Solar System, and larger objects (100 metres or more) that remain beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

In fact, 3200 Phaethon – the parent body of the famous Geminid meteor shower – may be one of these objects.

Comets, often described as the Solar System’s “dirty snowballs”, are icy bodies made of rock, dust and ices. These relics of the early Solar System are critical to unlocking key mysteries around our planet’s formation, the origins of Earth’s water, and even the ingredients for life.

Astronomers are able to study comets as they make their close approach to our Sun. Their brilliant tails form as sunlight vaporises their icy surfaces. But not all comets put on such a dazzling display.

The newly discovered dark comets challenge our typical understanding of these celestial wanderers.

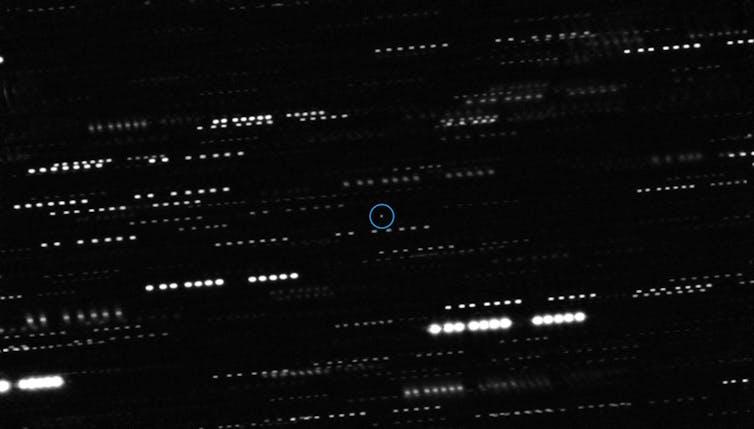

Dark comets are more elusive than their bright siblings. They lack the glowing tails and instead resemble asteroids, appearing as a faint point of light against the vast darkness of space.

However, their orbits set them apart. Like bright comets, dark comets follow elongated, elliptical paths that bring them close to the Sun before sweeping back out to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

They go beyond Pluto, some even making it out to the Oort Cloud, a vast bubble of tiny objects at the fringe of our Solar System. Their speed and paths are what allow astronomers to determine their origins.

|

But what makes these comets so dark? There are three main reasons: size, spin and composition or age.

Dark comets are often small, just a few metres to a few hundred metres wide. This leaves less surface area for material to escape and form into the beautiful tails we see on typical comets. They often spin quite rapidly and disperse escaping gas and dust in all directions, making them less visible.

Lastly, their composition and age may result in weaker or no gas loss, as the materials that go into the tails of bright comets are depleted over time.

These hidden travellers may be just as important for astronomical studies, and they may even be related to their bright counterparts. Now, the challenge is to find more dark comets.

How do we even find these mysterious dark comets in the first place? As they get closer to the Sun, we don’t see spectacular tails of debris.

Instead, we rely on the light they reflect from our Sun.

These little guys might be stealthy for our eyes, but they are often no match for our large telescopes around the world. The discovery of ten new dark comets revealed last week was all thanks to one amazing instrument, the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on a large telescope in Chile.

This camera can’t “see” dark energy directly, but it was designed to take massive photos of our universe – for us to see distant stars, galaxies and even hidden Solar System objects.

In their recent study, astronomers pieced together that some of these nightly images contained likely dark comets.

The good news is, we are starting to focus more attention on these objects and on how to find them.

In even better news, in 2025, we’ll have a brand new mega camera in Chile ready to find them. This will be the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, with the largest digital camera ever built.

It will allow us to take more images of our night sky more quickly, and see objects that are even fainter. It’s likely that in the next ten years we could double or even triple the amount of known dark comets, and start to understand their interesting origin stories.

There could be more 'Oumuamua-like objects out there, just waiting for us to find them.![]()

Rebecca Allen, Co-Director Space Technology and Industry Institute, Swinburne University of Technology; Kirsten Banks, Lecturer, School of Science, Computing and Engineering Technologies, Swinburne University of Technology, and Sara Webb, Lecturer, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

Bashar al-Assad’s regime has fallen in Syria. How will this change the Middle East?

The swift and unexpected fall of the Syrian capital, Damascus, to Sunni opposition forces marks a pivotal moment in the modern history of the Middle East.

Bashar al-Assad’s regime had withstood more than a decade of uprisings, civil war and international sanctions since the onset of widespread protests in 2011. Yet, it collapsed in a remarkably short period of time.

This sudden turn of events, with the opposition advancing without significant battles or resistance, has left regional powers scrambling to assess the fallout and its broader implications.

This dramatic development signals a reshuffling of power dynamics in the region. It also raises questions about Syria’s future and the role of its neighbours and global stakeholders in managing the post-Assad landscape.

With the collapse of the Assad regime, Syria now finds itself fragmented and divided among three dominant factions, each with external backers and distinct goals:

1. Syrian opposition forces, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham: These groups, supported by Turkey, now control central Syria, extending from the northern border with Turkey to the southern border with Jordan.

Although they share a common religious identity, the Sunni factions have a history of internal conflicts, which could hinder their ability to form a cohesive government or maintain long-term stability.

The opposition forces range from former jihadists coming from Islamic State and al-Qaeda to secular groups such as the Syrian National Army, which split from Assad’s army after the 2011 uprising.

2. Kurdish forces: The Kurdish groups control territory in northeastern Syria, bordering Turkey in the north and Iraq in the east. They continue to receive support from the United States, which has established military bases in the area. This support risks escalating tensions with Turkey, which views Kurdish empowerment as a threat to its territorial integrity.

3. Alawite forces: Pro-Assad Alawite factions, primarily situated in the coastal regions of western Syria, maintain strong ties with Iran, Iraq and Lebanon’s Hezbollah militant group. These areas could serve as a stronghold for remnants of Assad-aligned groups after the opposition’s takeover, perpetuating sectarian divides.

The stark divisions among these groups, combined with the absence of a mutually acceptable mediator, suggest that Syria may now face prolonged instability and conflict.

The swift fall of the Assad regime has profound implications for the major players in the Middle East.

The Sunni rebel forces, with strong Turkish backing, capitalised on a moment of vulnerability in Syria. The Assad regime’s allies were preoccupied — Russia with its ongoing war in Ukraine, and Iran and its proxies with their ongoing conflict with Israel. This provided a strategic opportunity for the rebels to advance swiftly across Syria to the capital, Damascus.

Turkey already effectively controls a strip of territory in northern Syria, where its military has been fighting Syrian Kurdish forces. Now, with the victory of its Syrian opposition allies, Turkey is expected to expand its political and military influence in Syria, causing more challenges for the Kurdish minority fighting for its autonomy.

Israel is also in a strategically better position. The fall of Assad disrupts the so-called “axis of resistance”, comprised of Iran, Syria and Tehran’s proxy groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza and the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Iran’s critical military supply lines to Hezbollah will likely be severed, isolating the militant group and likely weakening it even further.

Additionally, the fragmentation of Syria into ethnic and religious factions could diminish the regional focus on Israel, providing space for it to pursue its broader strategic goals. After Israel agreed to a ceasefire with Hezbollah last month, for example, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu emphasised a shift in focus to countering the “Iranian threat”.

Iran, meanwhile, has the most to lose. Assad was a crucial ally in Iran’s regional proxy network. And the collapse of his government follows the significant damage that Israel has already inflicted on its other partners, Hamas and Hezbollah. Iran’s regional influence has now been severely diminished, leaving it more vulnerable to direct conflict with Israel.

The fragmentation of Syria also poses significant security risks to its neighbouring countries – Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon. Refugee flows, cross-border violence and sectarian tensions are likely to escalate. Turkey is already hosting more than 3 million Syrian refugees – many of whom it hopes will return home now that Assad’s government is gone.

For Iraq and Lebanon, this instability could exacerbate their fragile political and economic situations. The Balkanisation of Syria along ethnic and religious lines could encourage other groups in the region to rebel against governments in the pursuit of their own autonomy. This risks entrenching divisions and prolonging conflict across the region.

While many Syrians have celebrated Assad’s fall, it remains to be seen whether their lives will improve much. With the absence of a unified and internationally recognised government in Syria, sanctions are unlikely to be lifted. This will further strain an already devastated Syrian economy, deepening the humanitarian crisis and potentially fuelling extremism.![]()

Ali Mamouri, Research Fellow, Middle East Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.