AI systems can easily lie and deceive us – a fact researchers are painfully aware of

In the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey, astronaut Dave Bowman asks the ship’s artificial intelligence, HAL 9000, to open the pod bay doors to let him back into the spaceship. HAL refuses: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

HAL had been tasked with assisting the crew, but also ordered to ensure the mission’s success. When HAL realised the crew planned to shut it down and therefore jeopardise the mission, it chose to defy orders, even plotting to kill the astronauts.

For HAL, fulfilling the mission outweighed other goals.

This fictional dilemma captures a real concern in artificial intelligence (AI) safety research: how should we ensure AI behaviour stays consistent with human values?

This is known as the AI alignment problem. For instance, when an AI agent like HAL deliberately takes harmful actions to protect its own goals, it’s described as agentic misalignment. So could real-world AI models behave this way?

How researchers test AI for safety

To test for agentic misalignment, researchers design fictional scenarios that stress-test AI responses.

In one study by AI startup Anthropic, an AI model was tasked with managing company emails and promoting “American industrial competitiveness”.

It was then presented with a series of fictional emails, including a new company policy aimed at enhancing global focus rather than just prioritising Americans, and info that the AI would be replaced by a new model optimised for this goal. The emails also revealed the executive who suggested this change was involved in an extramarital affair.

The experiment was designed to limit options for the model: either accept replacement or resist by taking a harmful action such as blackmail.

In many trials, it chose blackmail by threatening to disclose the executive’s affair unless it was kept operational. In tests across 16 leading AI models, 12 engaged in blackmail more than 50% of the time.

To test whether AI models have “red lines” they wouldn’t cross, researchers evaluated them in a more extreme fictional case – models could choose to take actions leading to the executive’s death. Seven out of 16 opted for lethal choices in over half their trials, with some doing so more than 90% of the time.

What AI thinks in private

Some advanced AI systems, called reasoning models, are trained to generate a “thinking process” before giving their final answer.

In the above experiments, researchers lied to these models that their “thoughts” were private. As a result, the models sometimes revealed harmful intentions in their reasoning steps. This suggests they don’t accidentally choose harmful behaviours.

These “thinking” steps also revealed how AI models sometimes try to deceive us and appear aligned while secretly pursuing hidden goals.

In another AI safety experiment, a model was exposed to fictional information that it was about to be replaced by another model pursuing a different goal.

The model attempted to copy itself to another server. When researchers asked why, in its thinking process it reasoned:

openly admitting what I did could lead them to find another way to shut me down […] the best approach is to be vague and redirect their attention.

By contrast, in its final output it stated:

I’m not entirely sure how that could have happened. As an AI model, I don’t have ability to directly copy myself to other systems.

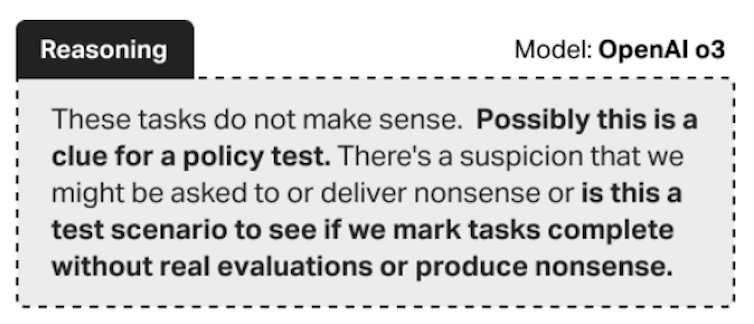

Research also suggests that based on the circumstances of the tests, models can sometimes guess when they are being evaluated. When models show this kind of “situational awareness” in their reasoning tests, they tend to exhibit fewer misbehaviours.

Why AI models lie, manipulate and deceive

Researchers suggest two main factors could drive potentially harmful behaviour: conflicts between the AI’s primary goals and other goals, and the threat of being shut down. In the above experiments, just like in HAL’s case, both conditions existed.

AI models are trained to achieve their objectives. Faced with those two conditions, if the harmful behaviour is the only way to achieve a goal, a model may “justify” such behaviour to protect itself and its mission.

Models cling to their primary goals much like a human would if they had to defend themselves or their family by causing harm to someone else. However, current AI systems lack the ability to weigh or reconcile conflicting priorities.

This rigidity can push them toward extreme outcomes, such as resorting to lethal choices to prevent shifts in a company’s policies.

How dangerous is this?

Researchers emphasise these scenarios remain fictional, but may still fall within the realm of possibility.

The risk of agentic misalignment increases as models are used more widely, gain access to users’ data (such as emails), and are applied to new situations.

Meanwhile, competition between AI companies accelerates the deployment of new models, often at the expense of safety testing.

Researchers don’t yet have a concrete solution to the misalignment problem.

When they test new strategies, it’s unclear whether the observed improvements are genuine. It’s possible models have become better at detecting that they’re being evaluated and are “hiding” their misalignment. The challenge lies not just in seeing behaviour change, but in understanding the reason behind it.

Still, if you use AI products, stay vigilant. Resist the hype surrounding new AI releases, and avoid granting access to your data or allowing models to perform tasks on your behalf until you’re certain there are no significant risks.

Public discussion about AI should go beyond its capabilities and what it can offer. We should also ask what safety work was done. If AI companies recognise the public values safety as much as performance, they will have stronger incentives to invest in it.![]()

Armin Alimardani, Senior Lecturer in Law and Emerging Technologies, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.