|

| Shutterstock |

Friday, 9 February 2024

Has the world crossed the 1.5C warming threshold already ?

Friday, 26 January 2024

Australia Day

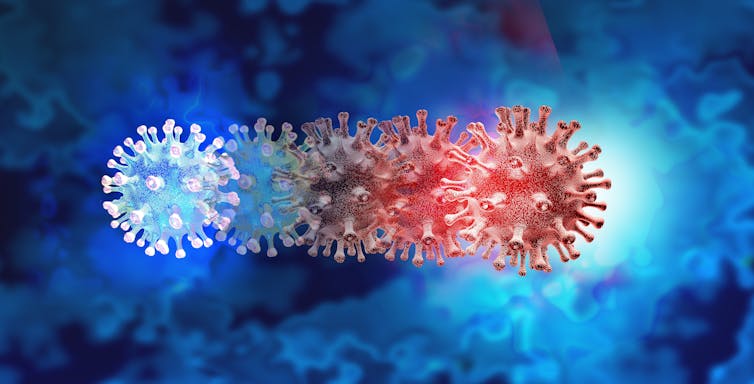

COVID evolution

The emergence of JN.1 is an evolutionary ‘step change’ in the COVID pandemic. Why is this significant?

Since it was detected in August 2023, the JN.1 variant of COVID has spread widely. It has become dominant in Australia and around the world, driving the biggest COVID wave seen in many jurisdictions for at least the past year.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified JN.1 as a “variant of interest” in December 2023 and in January strongly stated COVID was a continuing global health threat causing “far too much” preventable disease with worrying potential for long-term health consequences.

JN.1 is significant. First as a pathogen – it’s a surprisingly new-look version of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID) and is rapidly displacing other circulating strains (omicron XBB).

It’s also significant because of what it says about COVID’s evolution. Normally, SARS-CoV-2 variants look quite similar to what was there before, accumulating just a few mutations at a time that give the virus a meaningful advantage over its parent.

However, occasionally, as was the case when omicron (B.1.1.529) arose two years ago, variants emerge seemingly out of the blue that have markedly different characteristics to what was there before. This has significant implications for disease and transmission.

Until now, it wasn’t clear this “step-change” evolution would happen again, especially given the ongoing success of the steadily evolving omicron variants.

JN.1 is so distinct and causing such a wave of new infections that many are wondering whether the WHO will recognise JN.1 as the next variant of concern with its own Greek letter. In any case, with JN.1 we’ve entered a new phase of the pandemic.

Where did JN.1 come from?

The JN.1 (or BA.2.86.1.1) story begins with the emergence of its parent lineage BA.2.86 around mid 2023, which originated from a much earlier (2022) omicron sub-variant BA.2.

Chronic infections that may linger unresolved for months (if not years, in some people) likely play a role in the emergence of these step-change variants.

In chronically infected people, the virus silently tests and eventually retains many mutations that help it avoid immunity and survive in that person. For BA.2.86, this resulted in more than 30 mutations of the spike protein (a protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 that allows it to attach to our cells).

The sheer volume of infections occurring globally sets the scene for major viral evolution. SARS-CoV-2 continues to have a very high rate of mutation. Accordingly, JN.1 itself is already mutating and evolving quickly.

How is JN.1 different to other variants?

BA.2.86 and now JN.1 are behaving in a manner that looks unique in laboratory studies in two ways.

The first relates to how the virus evades immunity. JN.1 has inherited more than 30 mutations in its spike protein. It also acquired a new mutation, L455S, which further decreases the ability of antibodies (one part of the immune system’s protective response) to bind to the virus and prevent infection.

The second involves changes to the way JN.1 enters and replicates in our cells. Without delving in to the molecular details, recent high-profile lab-based research from the United States and Europe observed BA.2.86 to enter cells from the lung in a similar way to pre-omicron variants like delta. However, in contrast, preliminary work by Australia’s Kirby Institute using different techniques finds replication characteristics that are aligned better with omicron lineages.

Further research to resolve these different cell entry findings is important because it has implications for where the virus may prefer to replicate in the body, which could affect disease severity and transmission.

Whatever the case, these findings show JN.1 (and SARS-CoV-2 in general) can not only navigate its way around our immune system, but is finding new ways to infect cells and transmit effectively. We need to further study how this plays out in people and how it affects clinical outcomes.

Is JN.1 more severe?

The step-change evolution of BA.2.86, combined with the immune-evading features in JN.1, has given the virus a global growth advantage well beyond the XBB.1-based lineages we faced in 2023.

Despite these features, evidence suggests our adaptive immune system could still recognise and respond to BA.286 and JN.1 effectively. Updated monovalent vaccines, tests and treatments remain effective against JN.1.

There are two elements to “severity”: first if it is more “intrinsically” severe (worse illness with an infection in the absence of any immunity) and second if the virus has greater transmission, causing greater illness and deaths, simply because it infects more people. The latter is certainly the case with JN.1.

What next?

We simply don’t know if this virus is on an evolutionary track to becoming the “next common cold” or not, nor have any idea of what that timeframe might be. While examining the trajectories of four historic coronaviruses could give us a glimpse of where we may be heading, this should be considered as just one possible path. The emergence of JN.1 underlines that we are experiencing a continuing epidemic with COVID and that looks like the way forward for the foreseeable future.

We are now in a new pandemic phase: post-emergency. Yet COVID remains the major infectious disease causing harm globally, from both acute infections and long COVID. At a societal and an individual level we need to re-think the risks of accepting wave after wave of infection.

Altogether, this underscores the importance of comprehensive strategies to reduce COVID transmission and impacts, with the least imposition (such as clean indoor air interventions).

People are advised to continue to take active steps to protect themselves and those around them.

For better pandemic preparedness for emerging threats and an improved response to the current one it is crucial we continue global surveillance. The low representation of low- and middle- income countries is a concerning blind-spot. Intensified research is also crucial.![]()

Suman Majumdar, Associate Professor and Chief Health Officer - COVID and Health Emergencies, Burnet Institute; Brendan Crabb, Director and CEO, Burnet Institute; Emma Pakula, Senior Research and Policy Officer, Burnet Institute, and Stuart Turville, Associate Professor, Immunovirology and Pathogenesis Program, Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 16 January 2024

The warming of Antarctica

A heatwave in Antarctica totally blew the minds of scientists. They set out to decipher it – and here are the results

Dana M Bergstrom, University of WollongongClimate scientists don’t like surprises. It means our deep understanding of how the climate works isn’t quite as complete as we need. But unfortunately, as climate change worsens, surprises and unprecedented events keep happening.

In March 2022, Antarctica experienced an extraordinary heatwave. Large swathes of East Antarctica experienced temperatures up to 40°C (72°F) above normal, shattering temperature records. It was the most intense heatwave ever recorded anywhere in the world.

So shocking and rare was the event, it blew the minds of the Antarctic climate science community. A major global research project was launched to unravel the reasons behind it and the damage it caused. A team of 54 researchers, including me, delved into the intricacies of the phenomenon. The team was led by Swiss climatologist Jonathan Wille, and involved experts from 14 countries. The collaboration resulted in two groundbreaking papers published today.

The results are alarming. But they provide scientists a deeper understanding of the links between the tropics and Antarctica – and give the global community a chance to prepare for what a warmer world may bring.

Head-hurting complexity

The papers tell a complex story that began half a world away from Antarctica. Under La Niña conditions, tropical heat near Indonesia poured into the skies above the Indian Ocean. At the same time, repeated weather troughs pulsing eastwards were generating from southern Africa. These factors combined into a late, Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season.

Between late February and late March 2022, 12 tropical storms had brewed. Five storms revved up to become tropical cyclones, and heat and moisture from some of these cyclones mashed together. A meandering jet stream picked up this air and swiftly transported it vast distances across the planet to Antarctica.

Below Australia, this jet stream also contributed to blocking the eastward passage of a high pressure system. When the tropical air collided with this so-called “blocking high”, it caused the most intense atmospheric river ever observed over East Antarctica. This propelled the tropical heat and moisture southward into the heart of the Antarctic continent.

Luck was on Antarctica’s side

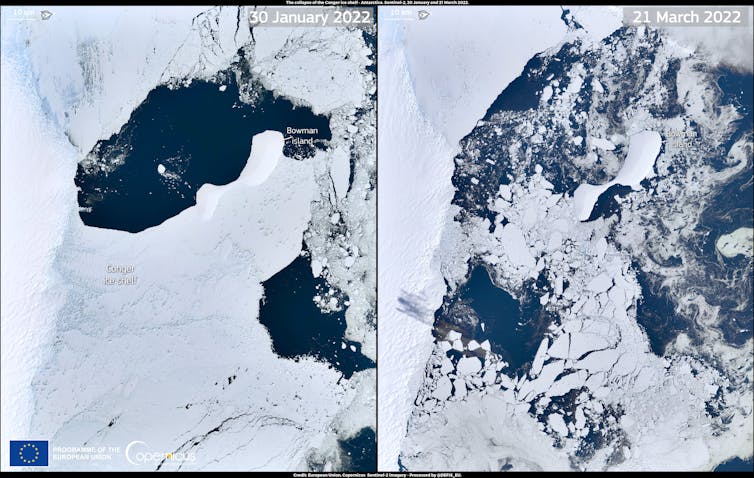

The event caused the vulnerable Conger Ice Shelf to finally collapse. But the impacts were otherwise not as bad as they could have been. That’s because the heatwave struck in March, the month when Antarctica transitions to its dark, extremely cold winter. If a future heatwave arrives in summer – which is more likely under climate change – the results could be catastrophic.

Despite the heatwave, most inland temperatures stayed below zero. The spike included a new all-time temperature high of -9.4°C (15.1°F) on March 18 near Antarctica’s Concordia Research Station. To understand the immensity of this, consider that the previous March maximum temperature at this location was -27.6°C (-17.68°F). At the heatwave’s peak, 3.3 million square kilometres in East Antarctica – an area about the size of India – was affected by the heatwave.

The impacts included widespread rain and surface melt along coastal areas. But inland, the tropical moisture fell as snow – lots and lots of snow. Interestingly, the weight of the snow offset ice loss in Antarctica for the year. This delivered a temporary reprieve from Antarctica’s contribution to global sea-level rise.

Learning from the results

So what are the lessons here? Let’s begin with the nice bit. The study was made possible by international collaboration across Antarctica’s scientific community, including the open sharing of datasets. This collaboration is a touchstone of the Antarctic Treaty. It serves as a testament to the significance of peaceful international cooperation and should be celebrated.

Less heartwarmingly, the extraordinary heatwave shows how compounding weather events in the tropics can affect the vast Antarctic ice sheet. The heatwave further reduced the extent of sea ice, which was already at record lows. This loss of sea ice was exacerbated this year resulting in the lowest summer and winter sea ice ever recorded. It shows how disturbances in one year can compound in later years.

The event also demonstrated how tropical heat can trigger the collapse of unstable ice shelves. Floating ice shelves don’t contribute to global sea-level rise, but they acts as dams to the ice sheets behind them, which do contribute.

This research calculated that such temperature anomalies occur in Antarctica about once a century, but concluded that under climate change, they will occur more frequently.

The findings enable the global community to improve its planning for various scenarios. For example, if a heatwave of similar magnitude hit in summer, how much ice melt would there be? If an atmospheric river hit the Doomsday glacier in the West Antarctic, what rate of sea level rise would that trigger? And how can governments across the world prepare coastal communities for sea level rise greater than currently calculated?

This research contributes another piece to the complex jigsaw puzzle of climate change. And reminds us all, that delays to action on climate change will raise the price we pay.

This article has been amended to correct an error in converting a 40°C temperature difference from Celsius to Fahrenheit.![]()

Dana M Bergstrom, Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sunday, 31 December 2023

2024 - The New Year beckons

|

| Shutterstock |

Friday, 29 December 2023

Conflict in 2024

Will the world see more wars or unrest in 2024? Here are 5 hotspots to watch

Jessica Genauer, Flinders UniversitySadly, 2023 has been a violent one on the global stage. War broke out between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, leading to the deaths of thousands of Palestinians and hundreds of Israelis, including many children on both sides. And the bitter war between Russia and Ukraine continued with no end in sight.

As a result of the focus on these two conflicts, other countries have dropped off the radar for many people. Some of these nations have been dealing with simmering unrest, however, which could erupt in 2024 and seize the global spotlight.

So, where should we be watching in the coming year? Here are five places where I believe civil conflicts or unrest could worsen and potentially lead to violence.

Myanmar

Myanmar descended into chaos in 2021 when a military coup overthrew the democratically elected government led by Aung San Suu Kyi and sparked widespread civil protests that eventually morphed into an armed resistance.

The country, home to 135 ethnic groups, has rarely known peace. For years before the coup, there was a ongoing, low-grade civil conflict between the military and several minority ethnic groups who have long sought control over natural resources in their regions and independence from the state.

This exploded after the coup as ethnic militia groups joined forces with pro-democracy fighters from the Bamar majority protesting the junta.

Their resistance escalated in late 2023 with a coordinated northern offensive dealing the military its most significant losses in many years.

Insurgents won control of towns and villages on the northeastern border with China, including control over key trade routes. This led to renewed fighting in western Rakhine state, as well as in other areas.

The tenacity of the resistance of these minority groups, paired with the refusal of the military to compromise, suggests the country’s civil war may worsen considerably in 2024 and regain international attention.

Mali

In Mali, a nation in the turbulent Sahel region of Africa, tensions escalated throughout 2023 and now threaten to erupt into full-scale civil war.

Mali has long battled insurgent activity. In 2012, Mali’s government fell in a coup and Tuareg rebels, backed by Islamist militants, seized power in the north.

A United Nations peacekeeping mission was established in 2013 to bring stability to Mali. Then, in 2015, key rebel groups signed a peace agreement with the Mali government.

After two more coups in 2020 and 2021, military officers consolidated their power and said they would restore the state’s full territorial control over all of Mali. The regime insisted the UN peacekeeping mission withdraw from the country, which it did in June 2023. Subsequently, violence broke out between the military and rebel forces over future use of the UN bases.

In November, the military, reportedly backed by Russia’s Wagner Group, took control of the strategic northern town of Kidal which had been held by Tuareg forces since 2012. This undermines the fragile peace that has held since 2015.

It is unlikely the military will regain complete control over all rebel-held areas in the north. At the same time, insurgents are emboldened. With the 2015 peace agreement now all but dead, we can expect increased volatility in 2024.

Lebanon

In 2019, widespread civil protest broke out in Lebanon against leaders who were perceived not to be addressing the day-to-day needs of the population.

The situation continued to deteriorate, with a reshuffled government, escalating economic crisis and a massive port explosion that exposed corrupt practices.

The International Monetary Fund criticised Lebanon in September for a lack of economic reform. The Lebanese government has also failed to reach agreement on appointing a president, a post that has been vacant for more than a year.

This risks undermining the fragile power-sharing arrangement in Lebanon in which the key political posts of prime minister, speaker and president are allocated to a Sunni-Muslim, Shia-Muslim and Christian Maronite, respectively.

Most recently, the war between Israel and Hamas has threatened to spill over to Lebanon, home to the Hezbollah militant group, which claims to have an army of 100,000 fighters. Importantly, this jeopardises tourism as a key hope for Lebanon’s economic recovery.

These factors may precipitate a more serious economic and political collapse in 2024.

Pakistan

Since Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the military has played an interventionist role in politics. Though Pakistani leaders are popularly elected, military officials have at times removed them from power.

In 2022, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan fell out of favour with Pakistan’s militant leaders. He was subsequently ousted from power in a parliament vote and later arrested on charges that his supporters claim are politically motivated.

Violent demonstrations broke out nationwide after his arrest – a display of anger against the military that was once unthinkable.

Pakistan also faces spillover from instability in neighbouring Afghanistan and increased terror attacks. These security challenges have been compounded by a struggling economy and ongoing costs from the devastating 2022 floods.

Pakistan is expected to hold parliamentary elections in February 2024, after which the current military caretaker government is expected to transfer power back to civilian rule. Many are watching the military closely. If this transfer of power does not take place, or there are delays, civil unrest may result.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka faced a debilitating economic crisis in 2022 that led to critical fuel, food and medical shortages. Civil protests caused then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee the country. He was quickly replaced by current President Ranil Wickremesingh.

Stability returned in 2023 as Sri Lanka began implementing economic reforms as part of a bailout agreement with the International Monetary Fund. However, widespread dissatisfaction with political elites and the underlying drivers of the country’s economic hardship have not been addressed.

Elections are also due in Sri Lanka by late 2024. While Wickremesingh, the incumbent, is likely to run for a second term, he has low trust with the public. He is viewed as too close to corrupt political elites.

This dissatisfaction could lead to renewed protests – particularly if the economy stumbles again – in a repeat of the situation that led to Rajapaksa’s ousting in 2022.![]()

Jessica Genauer, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.