|

| GPT-5 AI generated |

Sunday, 30 November 2025

Health - Exercise and walking to avoid Alzeheimers disease

Friday, 28 November 2025

Climate Change - COP30 ended with some results

This year’s climate talks saw real progress – just not on fossil fuels

It wasn’t a comfortable process for the tens of thousands of delegates trying to hash out progress on climate change on the edge of the Amazon in Belém, Brazil. I experienced the challenges of the United Nations COP30 climate talks firsthand.

Delegates were hot and sweaty. Tech and aircon didn’t always work. Both flood and fire disrupted negotiations over the fortnight of negotiations. It drove home how climate change feels. But despite the discomfort, some progress was made.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva dubbed it the “COP of Truth”. Delegates did not shy away from the urgency of the moment as climate change intensifies and emissions continue to climb.

Ahead of the talks, many feared global political headwinds and the United States’ departure from the Paris Agreement would undermine this year’s talks. The fact that nearly 60,000 delegates attended these talks – the second highest ever – shows this isn’t the case.

Progress was made on funding climate finance and adaptation to the changes already emerging. But efforts on ending reliance on fossil fuels faltered in the face of strong resistance by fossil fuel powers. Much progress in Belém happened outside the main talks.

So what did COP30 deliver?

At one stage it looked like COP30 might crack the hardest nut in climate policy – reaching agreement on phasing out fossil fuels. Nations agreed two years ago that it was necessary to move away from fossil fuels. But no plan had yet been devised to get there.

Brazil had a plan: build support for a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, championed by President Lula and pushed strongly by Environment Minister Marina Silva. It drew support from more than 80 countries, including major fossil fuel exporters such as Norway and Australia. Anticipating pushback, Brazil worked to boost support outside the main talks before bringing the plan in.

It didn’t work. By the end of COP30, all mention of a fossil fuel roadmap had been scrubbed from the text of the final outcomes, following fierce pushback from countries such as Russia, Saudi Arabia and India and many emerging economies.

Instead, countries agreed to launch “the Global Implementation Accelerator […] to keep 1.5°C within reach” and “taking into account” previous COP decisions. This initiative will be shepherded by the Brazilian COP30 Presidency and the leaders of next year’s COP31 talks, Turkey and Australia.

President Lula vowed to continue advocating for a fossil fuel roadmap at the G20. Colombia and the Netherlands will hold a conference on fossil fuel phaseout in April 2026. The COP30 decision text also makes reference to a “high-level event in 2026” which could take place in the Pacific. Without blockers of consensus at these meetings, a coalition of willing countries could make real progress in setting timelines and exchanging policy ideas for fossil fuel phase-out.

The decision to develop a just transition mechanism was welcomed as a win for workers and communities. The new mechanism’s purpose will be to increase international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building and knowledge-sharing as countries shift towards a low carbon global economy.

Efforts to boost financing for climate adaptation bogged down, reflecting the trade-offs over fossil fuels.

These funds are meant to help nations most exposed to severe climate damage, usually poorer and with low emissions. These nations led the charge for a tripling of climate finance by 2030 from the US$40 billion (A$62 billion) agreed at COP26 four years ago. But the agreed text merely “calls for efforts to at least triple adaptation finance by 2035”, which pushes out the timeframe and has no funding baseline.

Funding for tropical forests

One of Brazil’s own initiatives, the Tropical Forest Facility, achieved greater success, securing US$9.5 billion (A$14.7 billion) in funding pledges – a COP record.

The trust fund for rainforests is designed to provide resources to arrest global deforestation and protect Indigenous lands, including in the Amazon’s vital carbon sink.

Support for a roadmap towards ending deforestation secured 92 backers.

The success of these deforestation initiatives points to the effectiveness of the COP’s Action Agenda, aimed at spurring on climate action outside formal negotiations and including commitments from business, investors and civil society. As formal negotiations bog down, these bypasses may end up replacing negotiations in driving progress.

American absence

Ahead of COP30, analysts feared the ongoing attacks on climate action by the Trump administration would undermine the international negotiations.

COP30 was the first climate summit without a US government delegation. At first, the absence came as a relief.

But by summit’s end, the disappearance of the world’s biggest historical emitter and largest economy from negotiations had taken its toll.

Developing countries from the African group of negotiators argued better metrics and plans would be meaningless without funding to implement them. Traditionally, the US has been a major funder. No longer.

The US decision to turn its back on climate action created a subdued atmosphere. New finance pledges were broadly underwhelming, likely due to the dampening effect of the US retreat.

Early on, many hoped renewables and clean tech giant China might fill the leadership void. China’s clean tech exports last year were enough to cut overseas emissions by 1%. The huge industrial power produces almost 32% of the world’s carbon emissions. These emissions have plateaued, in turn suggesting global emissions may now have peaked.

But China showed reluctance to take up the mantle, preferring to remain focused on its own domestic energy transition. Chinese negotiators spent most of their energy pushing back against new European trade measures targeting emissions-intensive production.

It was left to some of the smallest nations, Indigenous peoples and civil society to lead calls for sticking to the science, ramping up urgency and accelerating the rollout of solutions. An estimated 70,000 people marched in the streets of Belém, staging a mock funeral for fossil fuels. It was an important affirmation of widespread public support for climate action.

What legacy?

As the UN’s climate Executive Secretary Simon Stiell said midway through COP30, nations had to “give a little to get a lot”.

Many countries will be reflecting they gave a lot but got very little. The biggest winners were, yet again, the world’s petrostates who successfully frustrated attempts to address fossil fuels.

Questions will inevitably be asked over whether these consensus-based talks are fit for purpose, given they can be gamed by blockers.

For many, COP30 will be regarded as a failure on fossil fuels and addressing major gaps between national pledges to cut emissions and what’s needed to hold warming to 1.5°C.

This is true. But another view would be that these talks made real progress on important areas despite considerable challenges.

Negotiators from 194 countries showed up and continued to talk and work together to tackle the worsening crisis. Nearly half of those countries have shown they’re ready to begin weaning themselves off fossil fuels through their support for the phase-out roadmap. They don’t have to wait for a UN consensus to act. Fossil fuel exporters only have power while other nations buy and rely on their products.

The world’s climate talks are now clearly moving away from arcane negotiations to the pressing real-world challenges of doing the work. In a rapidly warming world, all issues are becoming climate issues.![]()

Jacqueline Peel, Professor of Law, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Saturday, 15 November 2025

Environment - Climate Change - reduced carbon emissions in 35 countries

The world’s carbon emissions continue to rise. But 35 countries show progress in cutting carbon

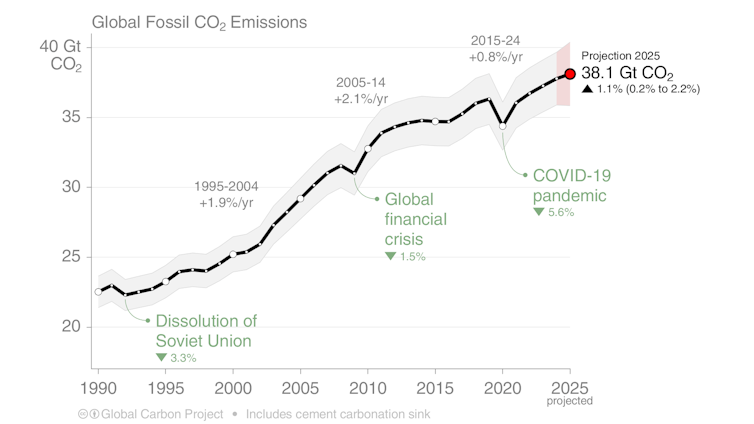

Global fossil fuel emissions are projected to rise in 2025 to a new all-time high, with all sources – coal, gas, and oil – contributing to the increase.

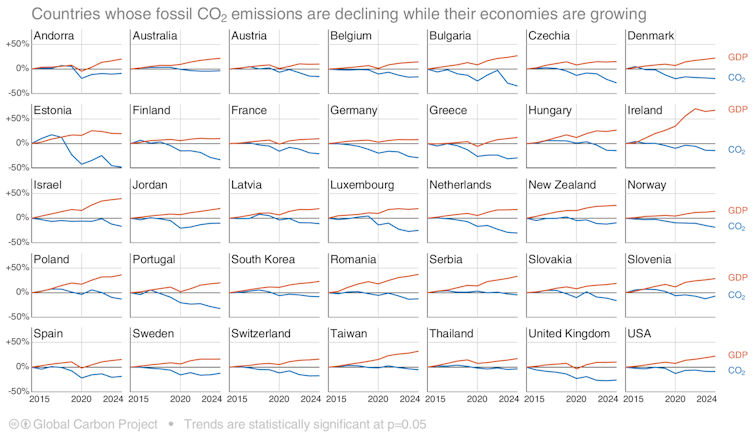

At the same time, our new global snapshot of carbon dioxide emissions and carbon sinks shows at least 35 countries have a plan to decarbonise. Australia, Germany, New Zealand and many others have shown statistically significant declines in fossil carbon emissions during the past decade, while their economies have continued to grow. China’s emissions have also been been growing at a much slower pace than recent trends and might even be flat by year’s end.

As world leaders and delegates meet in Brazil for the United Nations’ global climate summit, COP30, many countries that have submitted new emissions commitments to 2035 have shown increased ambition.

But unless these efforts are scaled up substantially, current global temperature trends are projected to significantly exceed the Paris Agreement target that aims to keep warming well below 2°C.

Fossil fuel emissions up again in 2025

Together with colleagues from 102 research institutions worldwide, the Global Carbon Project today releases the Global Carbon Budget 2025. This is an annual stocktake of the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide worldwide.

We also publish the major scientific advances enabling us to pinpoint the global human and natural sources and sinks of carbon dioxide with higher confidence. Carbon sinks are natural or artificial systems such as forests which absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they release.

Global CO₂ emissions from the use of fossil fuels continue to increase. They are set to rise by 1.1% in 2025, on top of a similar rise in 2024. All fossil fuels are contributing to the rise. Emissions from natural gas grew 1.3%, followed by oil (up 1.0%) and coal (up 0.8%). Altogether, fossil fuels produced 38.1 billion tonnes of CO₂ in 2025.

Not all the news is bad. Our research finds emissions from the top emitter, China (32% of global CO₂ emissions) will increase significantly more slowly below its growth over the past decade, with a modest 0.4% increase. Emissions from India (8% of global) are projected to increase by 1.4%, also below recent trends.

However, emissions from the United States (13% of global) and the European Union (6% of global) are expected to grow above recent trends. For the US, a projected growth of 1.9% is driven by a colder start to the year, increased liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, increased coal use, and higher demand for electricity.

EU emissions are expected to grow 0.4%, linked to lower hydropower and wind output due to weather. This led to increased electricity generation from LNG. Uncertainties in currently available data also include the possibility of no growth or a small decline.

Drop in land use emissions

In positive news, net carbon emissions from changes to land use such as deforestation, degradation and reforestation have declined over the past decade. They are expected to produce 4.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2025 down from the annual average of 5 billion tonnes over the past decade. Permanent deforestation remains the largest source of emissions. This figure also takes into account the 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon soaked up by human-driven reforestation annually.

Three countries – Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – contribute 57% of global net land-use change CO₂ emissions.

When we combine the net emissions from land-use change and fossil fuels, we find total global human-caused emissions will reach 42.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2025. This total has grown 0.3% annually over the past decade, compared with 1.9% in the previous one (2005–14).

Carbon sinks largely stagnant

Natural carbon sinks in the ocean and terrestrial ecosystems remove about half of all human-caused carbon emissions. But our new data suggests these sinks are not growing as we would expect.

The ocean carbon sink has been relatively stagnant since 2016, largely because of climate variability and impacts from ocean heatwaves.

The land CO₂ sink has been relatively stagnant since 2000, with a significant decline in 2024 due to warmer El Niño conditions on top of record global warming. Preliminary estimates for 2025 show a recovery of this sink to pre-El Niño levels.

Since 1960, the negative effects of climate change on the natural carbon sinks, particularly on the land sink, have suppressed a fraction of the full sink potential. This has left more CO₂ in the atmosphere, with an increase in the CO₂ concentration by an additional 8 parts per million. This year, atmospheric CO₂ levels are expected to reach just above 425 ppm.

Tracking global progress

Despite the continued global rise of carbon emissions, there are clear signs of progress towards lower-carbon energy and land use in our data.

There are now 35 countries that have reduced their fossil carbon emissions over the past decade, while still growing their economy. Many more, including China, are shifting to cleaner energy production. This has led to a significant slowdown of emissions growth.

Existing policies supporting national emissions cuts under the Paris Agreement are projected to lead to global warming of 2.8°C above preindustrial levels by the end of this century.

This is an improvement over the previous assessment of 3.1°C, although methodological changes also contributed to the lower warming projection. New emissions cut commitments to 2035, for those countries that have submitted them, show increased mitigation ambition.

This level of expected mitigation falls still far short of what is needed to meet the Paris Agreement goal of keeping warming well below 2°C.

At current levels of emissions, we calculate that the remaining global carbon budget – the carbon dioxide still able to be emitted before reaching specific global temperatures (averaged over multiple years) – will be used up in four years for 1.5°C (170 gigatonnes remaining), 12 years for 1.7°C (525 Gt) and 25 years for 2°C (1,055 Gt).

Falling short

Our improved and updated global carbon budget shows the relentless global increase of fossil fuel CO₂ emissions. But it also shows detectable and measurable progress towards decarbonisation in many countries.

The recovery of the natural CO₂ sinks is a positive finding. But large year-to-year variability shows the high sensitivity of these sinks to heat and drought.

Overall, this year’s carbon report card shows we have fallen short, again, of reaching a global peak in fossil fuel use. We are yet to begin the rapid decline in carbon emissions needed to stabilise the climate.![]()

Pep Canadell, Chief Research Scientist, CSIRO Environment; Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Clemens Schwingshackl, Senior Researcher in Climate Science, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor of Climate Change Science, University of East Anglia; Glen Peters, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo; Judith Hauck, Helmholtz Young Investigator group leader and deputy head, Marine Biogeosciences section at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Universität Bremen; Julia Pongratz, Professor of Physical Geography and Land Use Systems, Department of Geography, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich; Mike O'Sullivan, Lecturer in Mathematics and Statistics, University of Exeter; Pierre Friedlingstein, Chair, Mathematical Modelling of Climate, University of Exeter, and Robbie Andrew, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 13 November 2025

Community Values: World Kindness Day

At a time of social challenge and conflict in many regions of the world, the need for kindness is never more apparent.

Weblink for further information: World Kindness Day

Tuesday, 11 November 2025

Remembrance Day

|

| Shutterstock |

Friday, 7 November 2025

Environment - Climate Change - COP30 - Brazil - Expectations

Geopolitics, backsliding and progress: here’s what to expect at this year’s COP30 global climate talks

Along with delegates from all over the world, I’ll be heading to the United Nations COP30 climate summit in the Brazilian Amazon city of Belém. Like many others, I’m unsure what to expect.

This year, the summit faces perhaps the greatest headwinds of any in recent history. In the United States, the Trump administration has slashed climate science, cancelled renewable projects, expanded fossil fuel extraction and left the Paris Agreement (again). Trump’s efforts to hamstring climate action have made for extreme geopolitical turbulence, overshadowing the world’s main forum for coordinating climate action – even as the problem worsens.

Last year, average global warming climbed above 1.5°C for the first time. Costly climate-fuelled disasters are multiplying, with severe heatwaves, fires and flooding affecting most continents this year.

Climate talks are never easy. Every nation wants input and many interests clash. Petrostates and big fossil fuel exporters want to keep extraction going, while Pacific states despairingly watch the seas rise. But in the absence of a global government to direct climate policy, these imperfect talks remain the best option for coordinating commitment to meaningful action.

Here’s what to keep an eye on this year.

A smaller-than-usual COP?

A persistent criticism of the annual climate summits is that they have become too big and unwieldy – more a trade show and playground for fossil fuel lobbyists than an effective forum for multilateral diplomacy and action on climate change. One solution is to deliberately make these talks smaller.

The Belém conference may end up having a smaller number of delegates, though not by design so much as logistical headaches.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva backed the decision to invite the world to the Amazon to display how vital the massive rainforest is as a carbon sink. But Belém’s remote location on the northeast coast, limited infrastructure and shortage of hotels have seen prices soar, putting the conference out of reach for smaller nations, including some of the most vulnerable. These constraints could undermine the inclusive “Mutirão” (collective effort on climate change) sought by organisers.

Show me the money

Climate finance is a perennial issue at COP meetings. These funding pledges by rich countries are intended to help poorer countries reduce emissions, adapt to climate change or recover from climate disasters. Poorer countries have long called for more funding, given rich countries have done vastly more damage to the climate.

At COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan last year, a new climate finance goal was set for US$300 billion (~A$460 billion) to be raised annually by developed countries by 2035, with the goal of reaching $US1.3 trillion (~A$2 trillion) in funding from both government and private sources over the same period.

To deliver the second goal, negotiators laid out a “Baku to Belém” roadmap. The details are due to be finalised at COP30. But with the US walking away from climate action and the European Union wavering, many eyes will be on China and whether it will step into the climate leadership vacuum left by developed countries. The EU has only just reached agreement on a 2040 emissions reduction target and an “indicative” cut for 2035.

Climate finance will be the priority for many countries, as worsening disasters such as Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica and Typhoon Kalmaegi in the Philippines once again demonstrate the enormous human and financial cost of climate change.

The latest UN assessment indicates the need for this funding is outpacing flows by 12–14 times. In Belém, poorer countries will be hoping to land agreement on greater finance and support for adaptation. Work on a global set of indicators to track progress on adaptation – including finance – will be key.

Brazilian organisers hope to rally countries around another flagship funding initiative set to launch at COP30. The Tropical Forests Forever Facility would compensate countries for preserving tropical forests, with 20% of funds directed to Indigenous peoples and local communities who protect tropical forest on their lands. If it gets up, this fund could offer a breakthrough in tackling deforestation by flipping the economics in favour of conservation and protecting a huge store of carbon.

2035 climate pledges

Belém was supposed to be a celebration of ambitious new emissions pledges which would keep alive the Paris Agreement goal of holding warming to 1.5°C. Nations were originally due to submit their 2035 pledges (formally known as Nationally Determined Contributions) by February, with an extension given to September after 95 per cent of countries missed the deadline.

When pledges finally arrived in September, they were broadly underwhelming. Only half the world’s emissions were covered by a 2035 pledge, meaning the remaining emissions gap could be very significant. Australia is pledging cuts of 62–70% from 2005 emissions levels.

That’s not to say there’s no progress. A new UN report suggests countries are bending the curve downward on emissions but at a far slower pace than is needed.

How negotiators handle this emissions gap will be a litmus test for whether countries are taking their Paris Agreement obligations seriously.

Rise of the courts

Even as some countries back away from climate action, courts are increasingly stepping into the breach. This year, the International Court of Justice issued a rousing Advisory Opinion on states’ climate obligations under international law, including that national targets have to make an adequate contribution to meeting the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal. The court warned failing to take “appropriate action” to safeguard the climate system from fossil fuel emissions – including from projects carried out by private corporations – may be “an internationally wrongful act”. That is, they could attract international liability.

It will be interesting to see how this ruling affects negotiating positions at COP30 over the fossil fuel phase-out. At COP28 in 2023, nations promised to begin “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems”. If countries fail to progress the phase-out, accountability could instead be delivered via the courts. A new judgement in France found the net zero targets of oil and gas majors amount to greenwashing, while lawsuits aimed at making big carbon polluters liable for climate damage caused by their emissions are in the pipeline.

An Australia/Pacific COP?

A big question to be resolved is whether Australia’s long-running bid to host next year’s COP in Adelaide will get up. The bid to jointly host COP31 with Pacific nations has strong international support, but the rival bidder, Turkey, has not withdrawn.

If consensus is not reached at COP30, the host city would default back to Bonn in Germany, where the UN climate secretariat is based.

Outcome unknown

As climate change worsens, these sprawling, intense meetings may not seem like a solution. But despite headwinds and backsliding, they are essential. The world has made progress on climate change since 2015, due in large part to the Paris Agreement. What’s needed now on its tenth anniversary is a reinfusion of vigour to get the job done.![]()

Jacqueline Peel, Professor of Law, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 6 November 2025

Health - research finds genes act differently in the brains of men and women

Hundreds of genes act differently in the brains of men and women

Differences between men and women in intelligence and behaviour have been proposed and disputed for decades.

Now, a growing body of scientific evidence shows hundreds of genes act differently in the brains of biologically male or female humans. What this means isn’t yet clear, though some of the genes may be linked to sex-biased brain disorders such as Alheizmer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

These sex differences between male and female brains are established early in development, so they may have a role in shaping brain development. And they are found not only in humans but also in other primates, implying they are ancient.

Gene activity in male and female brains

Decades of research have confirmed differences between men and women in brain structure, function and susceptibility to mental disorders.

What has been less clear is how much of this is due to genes and how much to environment.

We can measure the influence of genetics by looking directly at the activity of genes in the brains of men and women. Now that we have the full DNA sequence of the human genome, it is comparatively easy to detect activity of any or all of the roughly 20,000 genes it contains.

Genes are lengths of DNA, and to be expressed their sequence must be copied (“transcribed”) into messenger RNA molecules (mRNA), which are then translated into proteins – the molecules that actually do the work that underpins the structure and function of the body.

So by sequencing all of this RNA (called the “transcriptome”) and lining up the base sequences to the known genes, we can measure the activity of every gene in a particular tissue – even an individual cell.

When scientists compared the transcriptomes in postmortem tissue samples from hundreds of men and women in 2017, they found surprisingly different patterns of gene activity. A third of our 20,000 genes were expressed more in one sex than the other in one or several tissues.

The strongest sex differences were in the testes and other reproductive tissues, but, surprisingly, most other tissues also showed sex biases. For instance, a subsequent paper showed very different RNA profiles in muscle samples from men and women, which correspond to sex differences in muscle physiology.

A study of brain transcriptomes published earlier this year revealed 610 genes more active in male brains, and 316 more active in female brains.

What genes show sex bias in the brain?

Genes on the sex chromosomes would be expected to show different activity between men (with an X chromosome and a Y chromosome) and women (with two X chromosomes). However, most (90%) sex-biased genes lie on ordinary chromosomes, of which both males and females have two copies (one from mum, one from dad).

This means some sex-specific signal must control their activity. Sex hormones such as testosterone and oestrogen are likely candidates, and, indeed, many sex-biased genes in the brain respond to sex hormones.

How are sex differences established in the brain?

Sex differences in brain gene activity appear early in the development of the foetus, long before puberty or even the formation of testes and ovaries.

Another 2025 study examined 266 post mortem fetal brains and found more than 1,800 genes were more active in males and 1,300 in females. These sets of sex-biased genes overlapped with those seen in adult brains.

This points to direct genetic effects from genes on the sex chromosomes, rather than hormone-driven differences.

Do these differences mean male and female brains work differently?

It would be remarkable if sex differences in the activity of so many genes were not reflected in some major differences in brain function between men and women. But we don’t know to what extent, or which functions.

Some patterns are emerging. Many female-biased genes have been found to encode neuron-associated processes, whereas male-biased genes are more often related to traits such as membranes and nuclear structures.

Many genes are sex-biased only in particular sub-regions of the brain, which suggests they have a sex-specific function only in those regions.

However, differences in RNA levels don’t always produce differences in proteins. Cells can compensate to maintain protein balance, meaning that not all RNA differences have functional outcomes. Sometimes, developmental processes differ between sexes but lead to the same end result.

Brain health

Of particular interest is the finding of a relationship between sex biases and sex differences in the susceptibility to some brain disorders.

Many genes implicated in Alzheimer’s disease are female-biased, perhaps accounting for the doubled incidence of this disease in women. Studies on rodents imply that expression of the male-only SRY gene in the brain exacerbates Parkinson’s disease.

Evolution of sex differences in brain gene function

These sex-biased gene expression patterns are by no means unique to humans. They have also been found in the brains of rats and mice as well as in monkeys.

The suites of male- and female-biased genes in monkeys overlap significantly with those of humans, implying that sex biases were established in a common ancestor 70 million years ago.

This suggests that natural selection favoured gene actions that promoted slightly different behaviours in our male and female primate ancestors – or perhaps even further back, in the ancestor of all mammals, or even all vertebrates.

In fact, sex differences in the expression of genes in the developing brain look to be ubiquitous in animals. They have been observed even in the humble nematode worm.![]()

Jenny Graves, Distinguished Professor of Genetics and Vice Chancellor's Fellow, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Saturday, 1 November 2025

Sentinel Owl - geographical access for October 2025

|

| Shutterstock |

Sentinel Owl access data for October 2025:

- Singapore: 18.9k

- United States: 6.94k

- Hong Kong: 4.85k

- Brazil: 3.16k

- Mexico: 1.33k

- India: 825

- Argentina: 335

- Indonesia: 216

- Ecuador: 159

- Malaysia: 144