| Sample 1 - AI created avatar - female |

| Sample 2 -AI created avatar - male |

| Sample 1 - AI created avatar - female |

| Sample 2 -AI created avatar - male |

|

| Shutterstock |

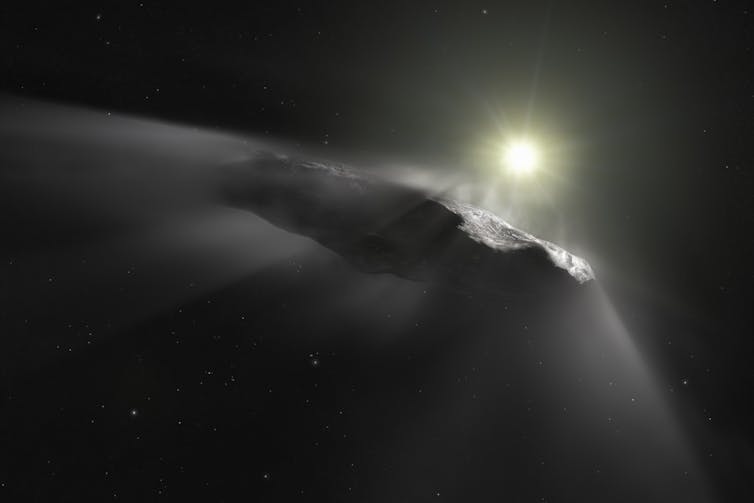

In 2017, NASA discovered and later confirmed the first interstellar object to enter our Solar System.

It wasn’t aliens. But artist impressions of the object (called ‘Oumuamua, the Hawaiian word for “scout”) do resemble an alien spaceship out of a sci-fi novel. This strange depiction is because astronomers don’t quite know how to classify the interstellar visitor.

Its speed and path around the Sun don’t match a typical asteroid, but it also has no bright tail or nucleus (icy core) we normally associate with comets. However, 'Oumuamua has erratic motions that are consistent with gas escaping from its surface. This “dark comet” has had astronomers scratching their heads ever since.

Flash forward to today, and more of these mysterious objects have been discovered, with another ten announced just last week. While their nature and origins remain elusive, astronomers recently confirmed dark comets fall into two main categories: smaller objects that reside in our inner Solar System, and larger objects (100 metres or more) that remain beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

In fact, 3200 Phaethon – the parent body of the famous Geminid meteor shower – may be one of these objects.

Comets, often described as the Solar System’s “dirty snowballs”, are icy bodies made of rock, dust and ices. These relics of the early Solar System are critical to unlocking key mysteries around our planet’s formation, the origins of Earth’s water, and even the ingredients for life.

Astronomers are able to study comets as they make their close approach to our Sun. Their brilliant tails form as sunlight vaporises their icy surfaces. But not all comets put on such a dazzling display.

The newly discovered dark comets challenge our typical understanding of these celestial wanderers.

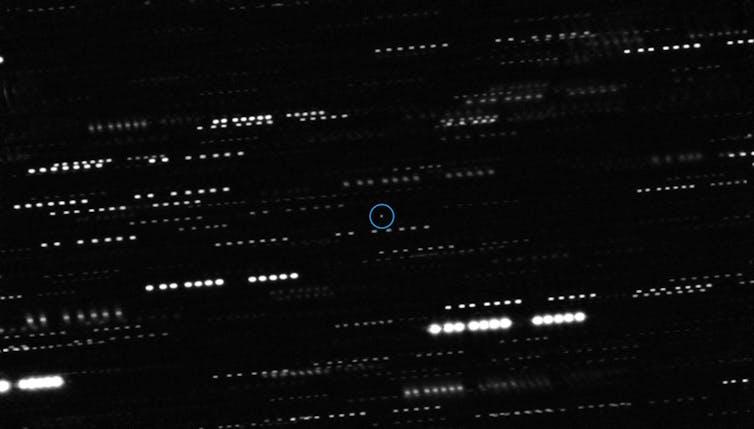

Dark comets are more elusive than their bright siblings. They lack the glowing tails and instead resemble asteroids, appearing as a faint point of light against the vast darkness of space.

However, their orbits set them apart. Like bright comets, dark comets follow elongated, elliptical paths that bring them close to the Sun before sweeping back out to the farthest reaches of the Solar System.

They go beyond Pluto, some even making it out to the Oort Cloud, a vast bubble of tiny objects at the fringe of our Solar System. Their speed and paths are what allow astronomers to determine their origins.

|

But what makes these comets so dark? There are three main reasons: size, spin and composition or age.

Dark comets are often small, just a few metres to a few hundred metres wide. This leaves less surface area for material to escape and form into the beautiful tails we see on typical comets. They often spin quite rapidly and disperse escaping gas and dust in all directions, making them less visible.

Lastly, their composition and age may result in weaker or no gas loss, as the materials that go into the tails of bright comets are depleted over time.

These hidden travellers may be just as important for astronomical studies, and they may even be related to their bright counterparts. Now, the challenge is to find more dark comets.

How do we even find these mysterious dark comets in the first place? As they get closer to the Sun, we don’t see spectacular tails of debris.

Instead, we rely on the light they reflect from our Sun.

These little guys might be stealthy for our eyes, but they are often no match for our large telescopes around the world. The discovery of ten new dark comets revealed last week was all thanks to one amazing instrument, the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on a large telescope in Chile.

This camera can’t “see” dark energy directly, but it was designed to take massive photos of our universe – for us to see distant stars, galaxies and even hidden Solar System objects.

In their recent study, astronomers pieced together that some of these nightly images contained likely dark comets.

The good news is, we are starting to focus more attention on these objects and on how to find them.

In even better news, in 2025, we’ll have a brand new mega camera in Chile ready to find them. This will be the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, with the largest digital camera ever built.

It will allow us to take more images of our night sky more quickly, and see objects that are even fainter. It’s likely that in the next ten years we could double or even triple the amount of known dark comets, and start to understand their interesting origin stories.

There could be more 'Oumuamua-like objects out there, just waiting for us to find them.![]()

Rebecca Allen, Co-Director Space Technology and Industry Institute, Swinburne University of Technology; Kirsten Banks, Lecturer, School of Science, Computing and Engineering Technologies, Swinburne University of Technology, and Sara Webb, Lecturer, Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock |

|

| Shutterstock |

Bashar al-Assad’s regime has fallen in Syria. How will this change the Middle East?

The swift and unexpected fall of the Syrian capital, Damascus, to Sunni opposition forces marks a pivotal moment in the modern history of the Middle East.

Bashar al-Assad’s regime had withstood more than a decade of uprisings, civil war and international sanctions since the onset of widespread protests in 2011. Yet, it collapsed in a remarkably short period of time.

This sudden turn of events, with the opposition advancing without significant battles or resistance, has left regional powers scrambling to assess the fallout and its broader implications.

This dramatic development signals a reshuffling of power dynamics in the region. It also raises questions about Syria’s future and the role of its neighbours and global stakeholders in managing the post-Assad landscape.

With the collapse of the Assad regime, Syria now finds itself fragmented and divided among three dominant factions, each with external backers and distinct goals:

1. Syrian opposition forces, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham: These groups, supported by Turkey, now control central Syria, extending from the northern border with Turkey to the southern border with Jordan.

Although they share a common religious identity, the Sunni factions have a history of internal conflicts, which could hinder their ability to form a cohesive government or maintain long-term stability.

The opposition forces range from former jihadists coming from Islamic State and al-Qaeda to secular groups such as the Syrian National Army, which split from Assad’s army after the 2011 uprising.

2. Kurdish forces: The Kurdish groups control territory in northeastern Syria, bordering Turkey in the north and Iraq in the east. They continue to receive support from the United States, which has established military bases in the area. This support risks escalating tensions with Turkey, which views Kurdish empowerment as a threat to its territorial integrity.

3. Alawite forces: Pro-Assad Alawite factions, primarily situated in the coastal regions of western Syria, maintain strong ties with Iran, Iraq and Lebanon’s Hezbollah militant group. These areas could serve as a stronghold for remnants of Assad-aligned groups after the opposition’s takeover, perpetuating sectarian divides.

The stark divisions among these groups, combined with the absence of a mutually acceptable mediator, suggest that Syria may now face prolonged instability and conflict.

The swift fall of the Assad regime has profound implications for the major players in the Middle East.

The Sunni rebel forces, with strong Turkish backing, capitalised on a moment of vulnerability in Syria. The Assad regime’s allies were preoccupied — Russia with its ongoing war in Ukraine, and Iran and its proxies with their ongoing conflict with Israel. This provided a strategic opportunity for the rebels to advance swiftly across Syria to the capital, Damascus.

Turkey already effectively controls a strip of territory in northern Syria, where its military has been fighting Syrian Kurdish forces. Now, with the victory of its Syrian opposition allies, Turkey is expected to expand its political and military influence in Syria, causing more challenges for the Kurdish minority fighting for its autonomy.

Israel is also in a strategically better position. The fall of Assad disrupts the so-called “axis of resistance”, comprised of Iran, Syria and Tehran’s proxy groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza and the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Iran’s critical military supply lines to Hezbollah will likely be severed, isolating the militant group and likely weakening it even further.

Additionally, the fragmentation of Syria into ethnic and religious factions could diminish the regional focus on Israel, providing space for it to pursue its broader strategic goals. After Israel agreed to a ceasefire with Hezbollah last month, for example, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu emphasised a shift in focus to countering the “Iranian threat”.

Iran, meanwhile, has the most to lose. Assad was a crucial ally in Iran’s regional proxy network. And the collapse of his government follows the significant damage that Israel has already inflicted on its other partners, Hamas and Hezbollah. Iran’s regional influence has now been severely diminished, leaving it more vulnerable to direct conflict with Israel.

The fragmentation of Syria also poses significant security risks to its neighbouring countries – Turkey, Iraq, Jordan and Lebanon. Refugee flows, cross-border violence and sectarian tensions are likely to escalate. Turkey is already hosting more than 3 million Syrian refugees – many of whom it hopes will return home now that Assad’s government is gone.

For Iraq and Lebanon, this instability could exacerbate their fragile political and economic situations. The Balkanisation of Syria along ethnic and religious lines could encourage other groups in the region to rebel against governments in the pursuit of their own autonomy. This risks entrenching divisions and prolonging conflict across the region.

While many Syrians have celebrated Assad’s fall, it remains to be seen whether their lives will improve much. With the absence of a unified and internationally recognised government in Syria, sanctions are unlikely to be lifted. This will further strain an already devastated Syrian economy, deepening the humanitarian crisis and potentially fuelling extremism.![]()

Ali Mamouri, Research Fellow, Middle East Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The petroleum-laden dust has settled on this year’s United Nations climate summit, COP29, held over the past fortnight in Baku, Azerbaijan. Climate scientists, leaders, lobbyists and delegates are heading for home.

The meeting achieved incremental progress. Negotiators agreed on a new climate finance target of at least US$300 billion a year by 2035 (A$460 billion), up from US$100 billion now. These funds would help developing nations shift away from fossil fuels, adapt to the warming climate and respond to loss and damage from climate disasters.

Nations also agreed on the essential rules for a global carbon trading market, the last agreement needed to make the 2015 Paris Agreement fully operational.

As UN climate chief Simon Stiell said in the final session, the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) meeting showed the Paris Agreement was delivering on climate action, but national governments “still need to pick up the pace”.

I attended COP29 as an expert in international climate law and litigation. I observed the finance negotiations firsthand and represented a new alliance of Australian and Pacific universities supporting international climate cooperation.

At the outset, expectations for the conference were low. The United States had just voted for the return of climate denier Donald Trump. And Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev declared oil and gas a “gift of God” at an opening event.

But even with these considerable headwinds, progress was made.

The world’s rich countries currently contribute US$100 billion a year to climate finance for developing nations. It pays for measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change by making systems more resilient.

Two years ago, countries agreed to create a new “loss and damage” fund for nations dealing with climate disasters, launched at the summit in Dubai last year.

At these COP29 talks, Australia announced it would contribute A$50 million (US$32 million) to this fund. Climate change is already costing developing countries huge sums, estimated at US$100-$500 billion a year.

These flows of funding from rich countries are essential for developing nations to increase their emissions reduction, as well as respond to climate damage.

The COP29 deal sets a target of at least US$300 billion per year by 2035, with richer countries leading delivery.

While this goal represents a tripling of the previous target, it falls far short of the $400-$900 billion many developing countries had called for in finance from rich governments.

Disappointed developing country representatives labelled it “a paltry sum” and a “joke”. It also falls short of what experts say is needed by 2035 to meet global climate finance needs.

Recognising this gap, the text calls on “all actors to work together” to scale up finance from all public and private sources to at least US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035. Ways this might be achieved will be presented at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, a year from now.

COP29 also reached an agreement that settles longstanding disputes about making the international carbon market a reality. This hard-won deal delivered global standards for carbon trading, opening up new ways for developing countries to boost their renewable energy capacity.

These rules will pave the way for country-to-country trading of carbon credits. Each credit represents a tonne of carbon dioxide either removed from the atmosphere or not emitted. The deal will give countries more flexibility in how they meet their emissions targets.

It’s not perfect. Concerns linger on whether the rules will ensure trades reflect real projects and how transparent and accountable the market will be.

But the agreement will boost the importance of carbon credits and could increase incentives to protect carbon “sinks” – such as rainforests, seagrass meadows and mangroves – with flow-on nature benefits.

By February 2025, all 195 Paris signatories have to announce more ambitious emission targets. Some countries announced their new plans at COP29.

The most ambitious was the United Kingdom, which upped its 2030 goal of a 68% cut to reducing 81% below 1990 emissions by 2035.

Next year’s host, Brazil, released new targets for a 59%–67% drop below 2005 levels by 2035.

But Brazil didn’t amend its 2030 ambitions and plans to boost oil and gas production 36% by 2035.

The United Arab Emirates announced target cuts of 47% before 2035, ahead of net zero by 2050. But this pledge was criticised by climate campaigners because the UAE is projected to boost oil and gas production 34% by by 2035.

The host, Azerbaijan, did not release its goals. Many other countries, including Australia, also held off from announcing new targets in Baku.

Fossil fuels were the elephant in the room. At last year’s COP in Dubai, nations finally agreed to include wording on:

transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science

But at this year’s COP, there was no decision on how, exactly, to begin this transition – and fossil fuels are not explicitly mentioned in the outcome documents.

Delegates from oil giant Saudi Arabia repeatedly tried to block mention of fossil fuels across all of the negotiating streams.

The consequences of Trump’s re-election for climate action were much discussed. But I observed a surprising amount of acceptance and even optimism for climate cooperation.

The US is the world’s second-largest emitter, after China. Trump has promised to ramp up the country’s oil and gas production, and pull the US from the Paris Agreement as he did during his first term.

But climate action continued regardless – especially in renewables giant China, which hit its 2030 renewable target this year. The US is no longer the main player in climate negotiations, and many countries are much further down the road of cutting emissions. Few show signs of backtracking.

As the US bows out, it creates a vacuum. At COP29, middle powers such as Canada, the UK and Australia stepped up.

Negotiators from a progressive High Ambition Coalition – including small island states, the European Union and Latin American countries such as Columbia – played an important role in pushing to urgently increase finance for climate action.

China, for its part, is clearly eyeing off the position of climate leader about to be vacated by the US. And leaders of progressive US states attended COP29 to show parts of the US are still on board with climate action.

Australia’s bid to host COP31 in 2026 alongside Pacific nations was tipped to win, given it had the support from nearly all of the 29 “Western European and Other States” group of nations which will decide the host this time. Many observers expected an announcement at the end of COP29.

But no decision was made, as the rival bidder, Türkiye, did not withdraw its bid.

An announcement is now likely in mid-2025 – after Australia’s next federal election.

Many people are disappointed by COP29. It did not bring transformative change. The huge jump in climate finance called for by developing countries, and many in civil society, didn’t eventuate.

It came as 2024 is on track to be the hottest on record, and the costs of extreme weather have risen to more than US$2 trillion over the last decade.

But this year’s talks were still a step forward, affirming international climate cooperation at a time of significant geopolitical tensions globally. As the UN’s Simon Stiell said:

the UN Paris Agreement is humanity’s life-raft; there is nothing else […] We are taking that journey forward together.

Jacqueline Peel, Director, Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Last week, three tiny Australian satellites from Curtin University’s Binar Space Program burned up in Earth’s atmosphere. That was always going to happen. In fact, Binar means “fireball” in the Noongar language of the First Nations people of Perth.

When a satellite is in low Earth orbit (2,000km or less), it experiences orbital decay as it drags closer and closer to the surface, eventually burning up.

But these cube satellites (CubeSats), known as Binar-2, 3 and 4, entered the atmosphere much sooner than originally planned. They only lasted for two months – a third of what was expected. This significantly reduced valuable time for science and testing new systems.

The reason for their untimely demise? Our Sun has kicked into high gear, and the Binar satellites are far from the only casualty. Recent high solar activity has been causing an unexpected headache for satellite operators in the last few years, and it’s only increasing.

Solar activity includes phenomena such as sunspots, solar flares and solar wind – the stream of charged particles that flows toward Earth.

This activity is a product of the Sun’s ever-changing magnetic field, and approximately every 11 years, it completely flips. At the midpoint of this cycle, solar activity is at its highest.

While this cycle is known, specific solar activity is challenging to predict – the dynamics are complex and solar forecasting is in its infancy.

In the last few months, indicators of solar activity were more than one and a half times higher than predictions for this point in the current cycle, labelled solar cycle 25.

Space weather refers to the environmental effects that originate from outside our atmosphere (mostly the Sun). It affects us on Earth in a variety of noticeable and unnoticeable ways.

The most obvious is the presence of auroras. In the past few months, auroras have been visible far more intensely and closer to the equator than in the last two decades. This is a direct result of the increased solar activity.

Space weather, and solar activity in particular, also creates additional challenges for satellites and satellite operators.

Higher solar activity means more solar flares and stronger solar wind – resulting in a higher flux of charged particles that can damage or disrupt electrical components on satellites.

It also means an increase in ionising radiation, resulting in a higher dose for astronauts and pilots, and potential disruptions to long-distance radio communications.

But for satellites in low Earth orbit, the most consistent effect of solar activity is that the extra energy gets absorbed into the outer atmosphere, causing it to balloon outward.

As a result, all satellites less than 1,000km from Earth experience a significant increase in atmospheric drag. This is a force that disrupts their orbit and causes them to fall towards the planet’s surface.

Notable satellites in this region include the International Space Station and the Starlink constellation. These satellites have thrusters to counteract this effect, but these corrections can be expensive.

Low Earth orbit also contains many university satellites, such as the Binar CubeSats. Cube satellites are rarely equipped with tools that can adjust their altitude, so they’re entirely at the mercy of space weather.

The Binar Space Program is a satellite research program operating out of Curtin University. It aims to advance our understanding of the Solar System and lower the barrier for operating in space.

The program began operations with its first satellite, Binar-1, in September 2021. This was less than a year into solar cycle 25 when solar activity was relatively low.

In these conditions, the ten-centimetre cube satellite started at an altitude of 420km and survived a full 364 days in orbit.

The program’s follow-up mission – Binar-2, 3, and 4 – were three equally sized CubeSats. However, they were expected to last approximately six months owing to the extra surface area from new deployable solar arrays and a forecast increase in solar activity.

Instead, they only made it to two months before burning up. While cube satellite missions are relatively cheap, the premature ending of a mission will always be costly. This is even more true for commercial satellites, highlighting the need for more accurate space weather forecasting.

The good news is the Sun will calm down again. Despite the current unexpectedly high solar activity, it will likely slow down by 2026, and is expected to return to a solar minimum in 2030.

While this was not an explicit goal of the mission, the Binar Space Program has now poignantly demonstrated the dramatic effects of solar activity on space operations.

While the untimely loss of Binar-2, 3 and 4 was unfortunate, work has already begun on future missions. They are expected to launch into far more forgiving space weather.![]()

Kyle McMullan, PhD Candidate in Aerospace Engineering, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The next major United Nations meeting on climate change, known as COP29, is about to get underway in Baku, Azerbaijan. These annual meetings are the key international summits as the world attempts to address the unfolding climate crisis.

The talks this year are crucial as climate change worsens. In recent years, a series of climate-fuelled disasters and extreme events, from Australia’s bushfires to Spain’s floods, have wrought havoc around the world.

What’s more, the continuing upward trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions suggests the window to limit warming 1.5°C is almost closed. And the re-election of United States President Donald Trump casts a pall over global climate action.

So, let’s take a look at the agenda for this vital COP meeting – and how we can gauge its success or failure.

COP stands for Conference of the Parties, and refers to the nearly 200 nations that have signed up to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Like last year’s conference in Dubai, the choice to hold this year’s meeting in Baku is controversial. Critics say Azerbaijan’s status as a “petro-state” with a questionable human rights record means it is not a suitable host.

Nevertheless, the meeting is crucial. COP29 has been dubbed the “finance COP”. The central focus is likely to be a much bigger target for climate finance – a mechanism by which wealthy countries provide funding to help poorer countries with their clean energy transition and to strengthen their climate resilience.

At the Copenhagen COP talks in 2009, developed countries committed to collectively providing US$100 billion a year for climate finance. This was seen as the big outcome of otherwise unsuccessful talks – but these targets are not being met.

The meeting also represents an opportunity to engage the private sector to play a bigger role in driving investment in the renewable energy transition.

But controversial questions remain. Who should be giving money and receiving it? And how do we ensure wealthy countries actually make good on their commitments?

The big outcome from last year’s COP was the establishment of a fund for unavoidable loss and damage experienced by vulnerable states as a result of climate effects. We’ve since seen some progress in clarifying how it will work.

But the US$700 million committed to the fund is far short of what is already required – and finance required is certain to increase over time. One estimate suggested US$580 billion will be needed by 2030 to cover climate-induced loss and damage.

Alongside these issues, the Baku talks will hopefully see some movement on adaptation finance, enabling further funds for building climate resilience in developing countries. To date, contributions and commitments have been well short of the goal set in 2021.

A final issue will be how to clarify rules around carbon markets, especially on the controversial topic of whether nations can use carbon trading to meet their Paris Agreement emission cut targets.

Talks on the latter have been stalled for years. Some analysts see movement on carbon markets as crucial for building momentum for the transition from fossil fuels.

By far the biggest shadow over the Baku talks is the election of Republican Donald Trump as United States president.

Trump famously withdrew the US from the climate agreement in 2016, and has declared climate change as “one of the greatest scams of all time”.

Trump’s re-election will significantly affect US cooperation on climate change at a time when the stakes for the planet could barely be higher.

More broadly, geopolitical tensions and conflicts – from Gaza to Ukraine – also risk crowding out the international agenda and undermining the chance of cooperation between key players.

This especially applies to Russia and China, both of which are crucial to international climate efforts.

At past COPs, difficult geopolitics elsewhere haven’t been fatal for cooperation on climate policy – but it does make things harder. For this reason, Azerbaijan has called for a “truce” in global conflicts to coincide with the conference.

This COP represents the last big climate talks before national governments have to publicly state their new emission cut goals – known as “nationally determined contributions” – which are due in February 2025.

A few big players – such as Brazil, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates – have already indicated they’ll be announcing their new targets at Baku.

There will also be plenty of pressure on other nations to ramp up their targets. That’s because existing commitments put the world far off track to meeting the globally agreed target of limiting planetary warming to 1.5°C – a threshold beyond which devastating climate harms are expected.

The host nation Azerbaijan is also keen to increase transparency around reporting obligations for countries, to make it easier to track progress against emissions targets.

Australia will almost certainly not be outlining a new emissions target in Baku. It has already signalled it may announce its updated targets after the February 2025 deadline.

For Australia, the main issue at Baku may be whether we – alongside at least one Pacific country – will be announced as the hosts of COP31 in 2026. Australia is tipped to win, but Turkey is a significant competitor.

Azerbaijan sees agreement on a new collective quantified goal for climate finance as the most important outcome of the conference.

This and other finance outcomes will be important in ensuring a fair distribution of costs from the impact of climate change and the necessary energy transition.

Action on long stalled carbon trading cooperation would also be a win, and could turbocharge the global energy transition.

But real success would come in the form of significant new emissions targets and explicit endorsement of the need to move away from fossil fuels. Sadly, the latter is not prominent on the Baku agenda.

Humanity has run out of time to prevent climate change, and we are already seeing real damage. But an opportunity remains to minimise the future harm. We must pursue urgent and sustained international action, regardless of who is in the White House.![]()

Matt McDonald, Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

|

| Shutterstock - Australian War Memorial |

|

| Shutterstock Donald J Trump |

The Lowy Institute, is an Australian thank tank with a global outlook and has produced a detailed interactive set of resources on the possible directions of the second presidency of Donald J Trump in the United States. It was developed in August by a team of experts in different fields before the 2024 presidential election. The information presented covers a range of issues such as international relations between the US and various regions (Australia, China, South-East Asia, Middle East, Ukraine), global climate policy, the world economy and the multilateral system. It can be found at the link below:

Lowy Institute: Donald Trump 2nd Presidency

|

| Shutterstock Donald J Tump in 2024 |

The US Presidential and Congressional Elections (and a multitude of other elected positions across the United States) have concluded. Trump was the clear winner in the presidential ballot securing well over the 270 electoral college votes with a minimum of 295 with one state still in counting at the date of this blog entry. The Republican Party looks to have succeeded in gaining a majority in both houses of Congress.

|

| BOM/CSIRO 2024 |

|

| Shutterstock |

Economics of the US: a key impression amongst voters is that the US economy is going backwards and interest rates are still increasing. This is not true and the US central bank, the Fed, has been reducing interest rates as the US economy is quite strong with a stable jobs market. In October 2024, 12,000 new jobs were created. However for the average US voter, day-to-day life still seems unaffordable and increasingly costly. Trump has promoted a view of economic malaise and the loss of jobs due to other countries/globalisation in the US despite the converse being true and this campaign tactic has been successful to a large degree with his core voter support.

November 5, 2024 beckons.....

UPDATED on 5 November 2024

Voting has been been occuring on polling day in the US. Over 80 million voters have now voted in the pre-poll (postal and in person at voting centres). The election contest continues to be impossible to call between Vice President Kamala Harris and former president Donald J Tump. There have been some surprising late poll data that came to light in Iowa which showed support for Harris increasing in an otherwise Republican State however whether this is replicated in the ballot box is yet to be determined.